drawings: Anna Pilawska-Sita

photographs: Michał Sita

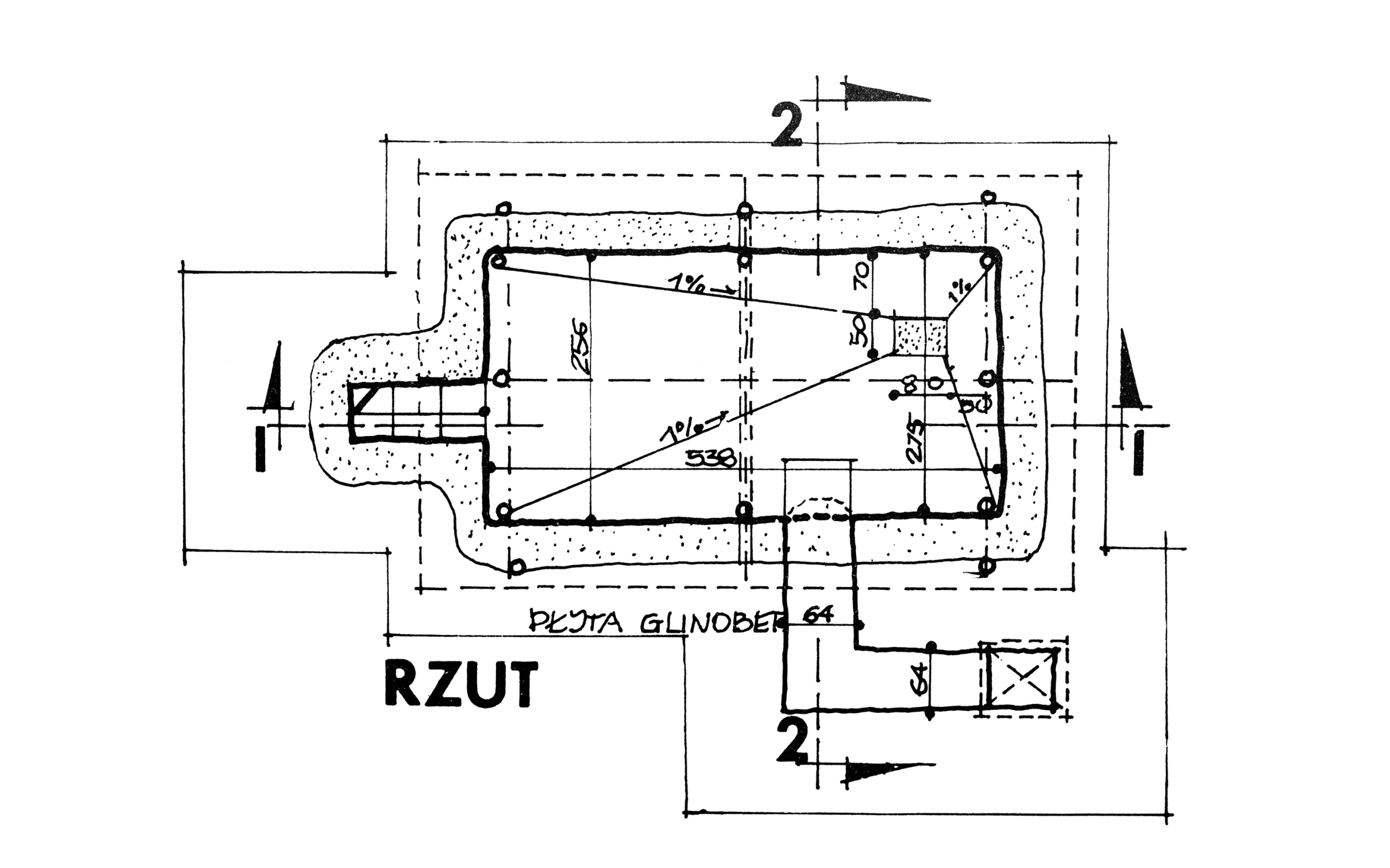

1982 technical drawings and photographs: Kazimierz Kwiatkowski

DTP: Marcin Markowski

translation: Agata Lewandowska

publisher: PIX.HOUSE, Poznań 2019

ISBN: 978–83-952480–9‑2

format: 17 x 22,7 cm, 84 pages

print run: 300

language: English

The book price includes shipping. You can pay directly with PayPal. After purchase please fill in the delivery address in the PayPal form.

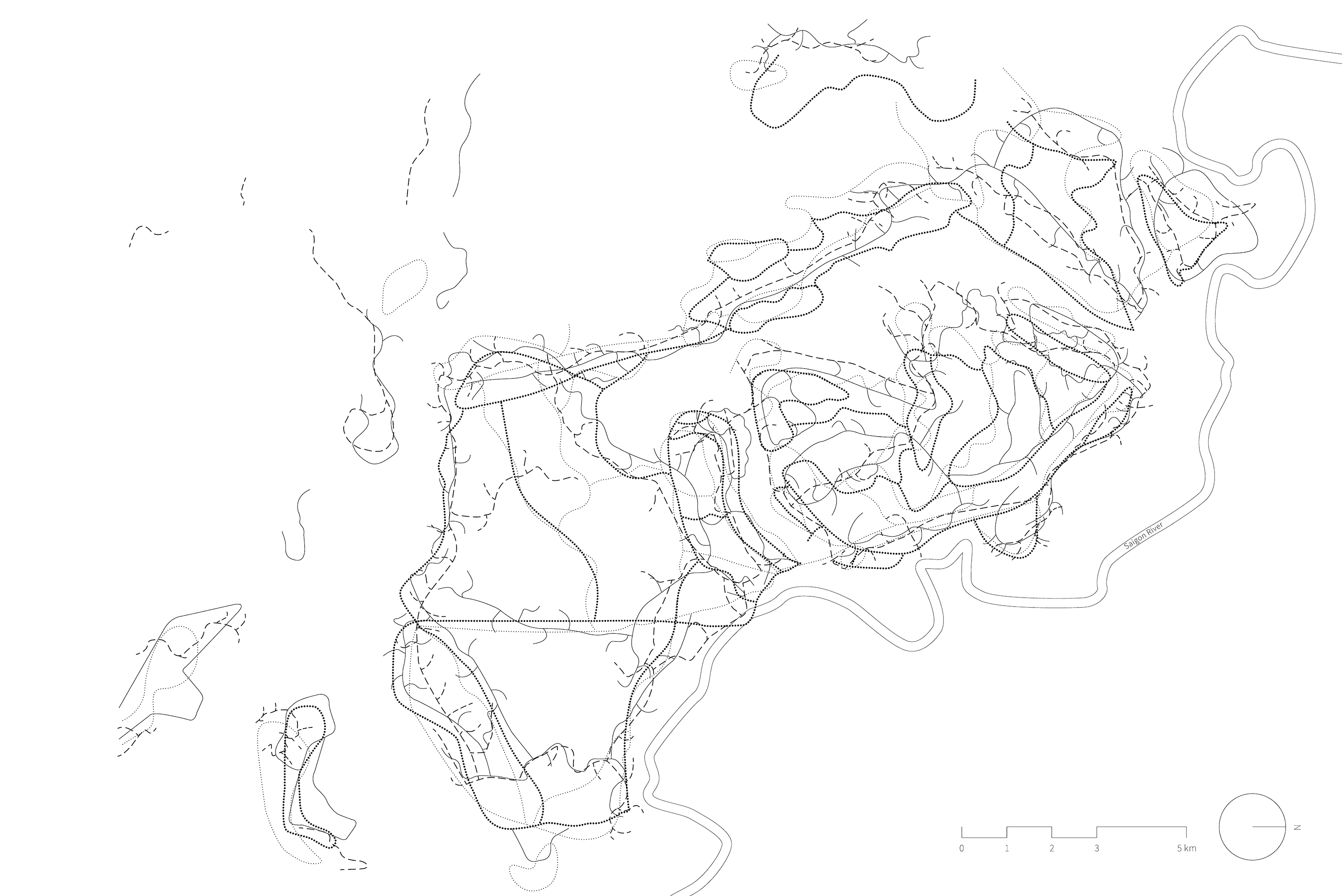

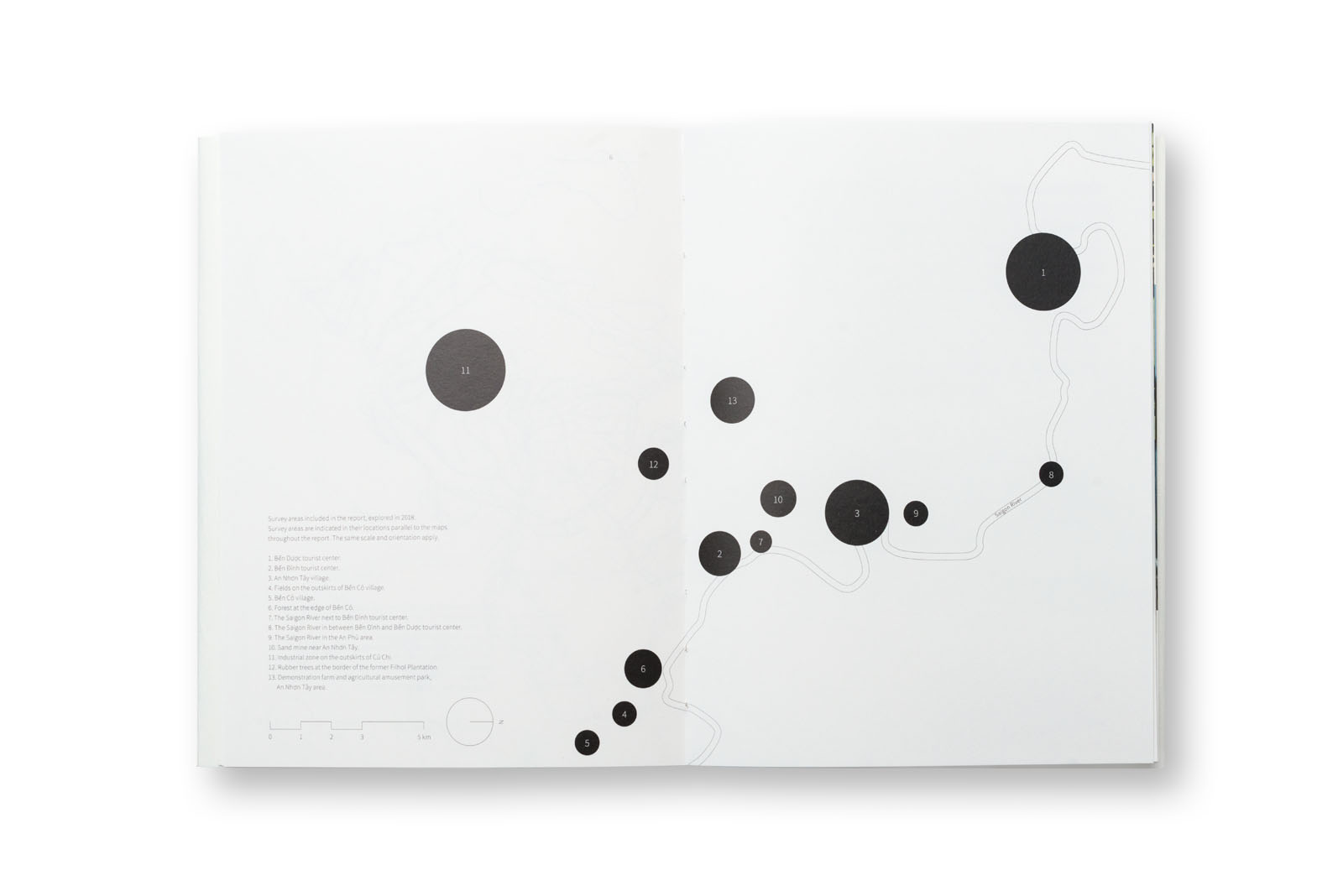

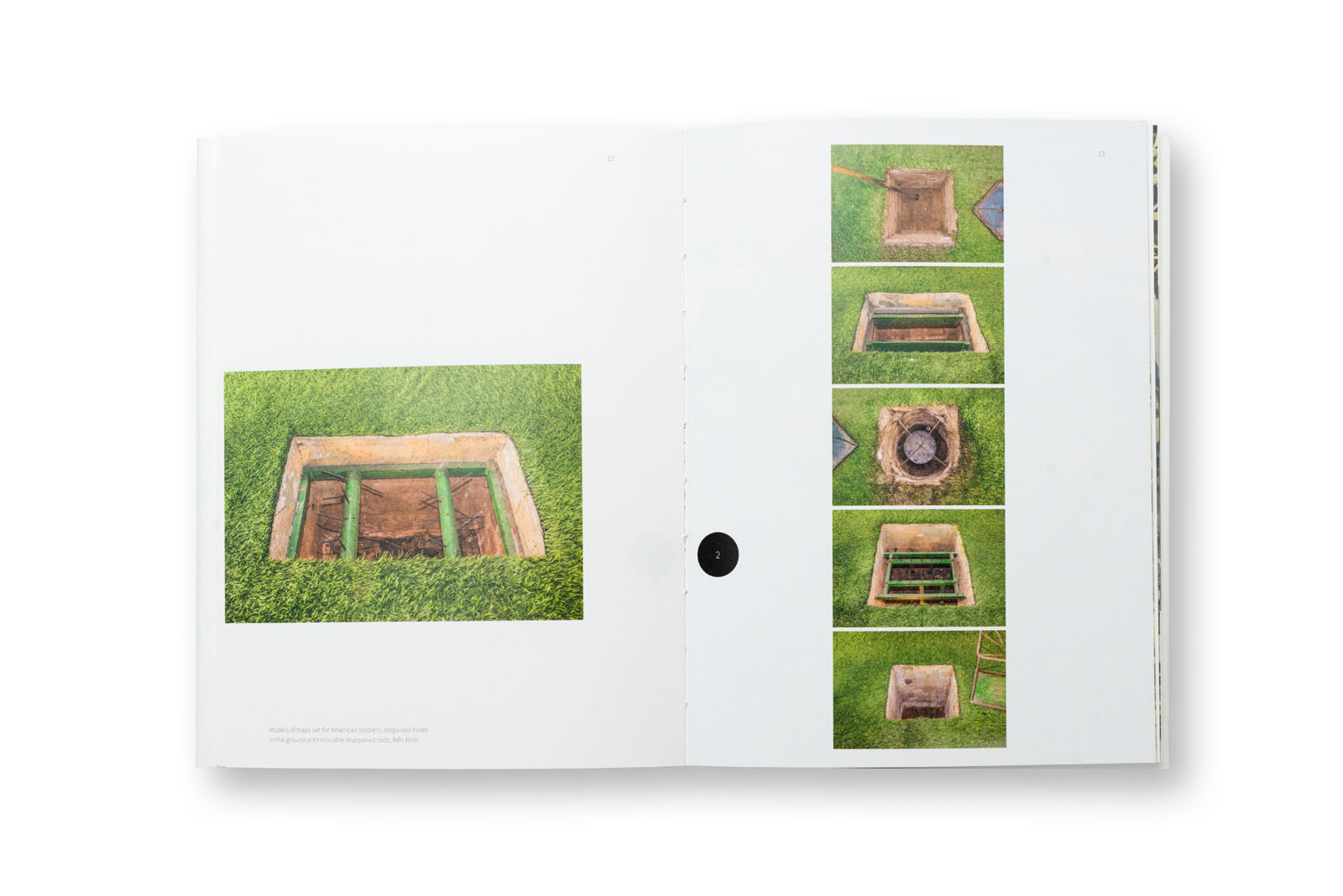

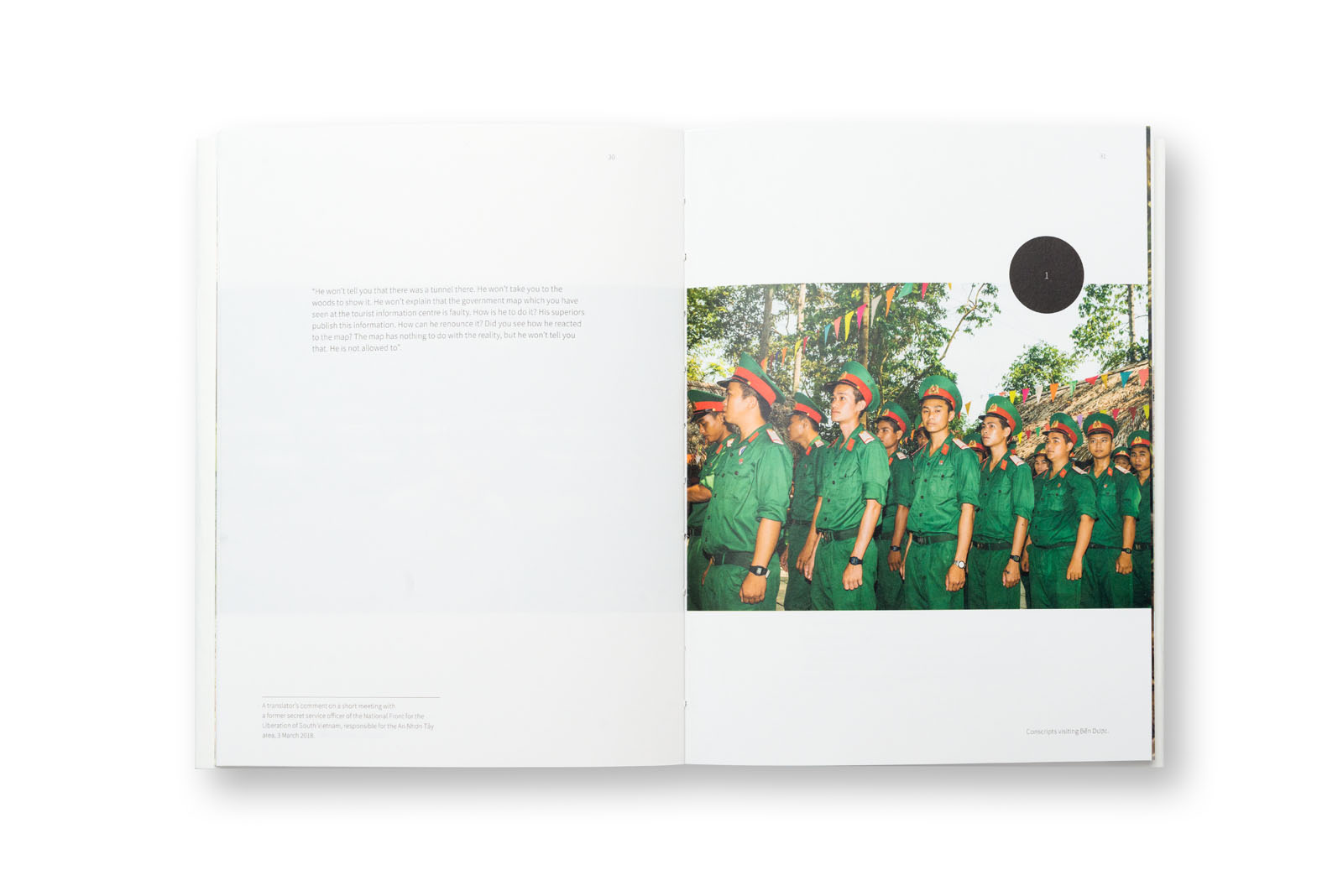

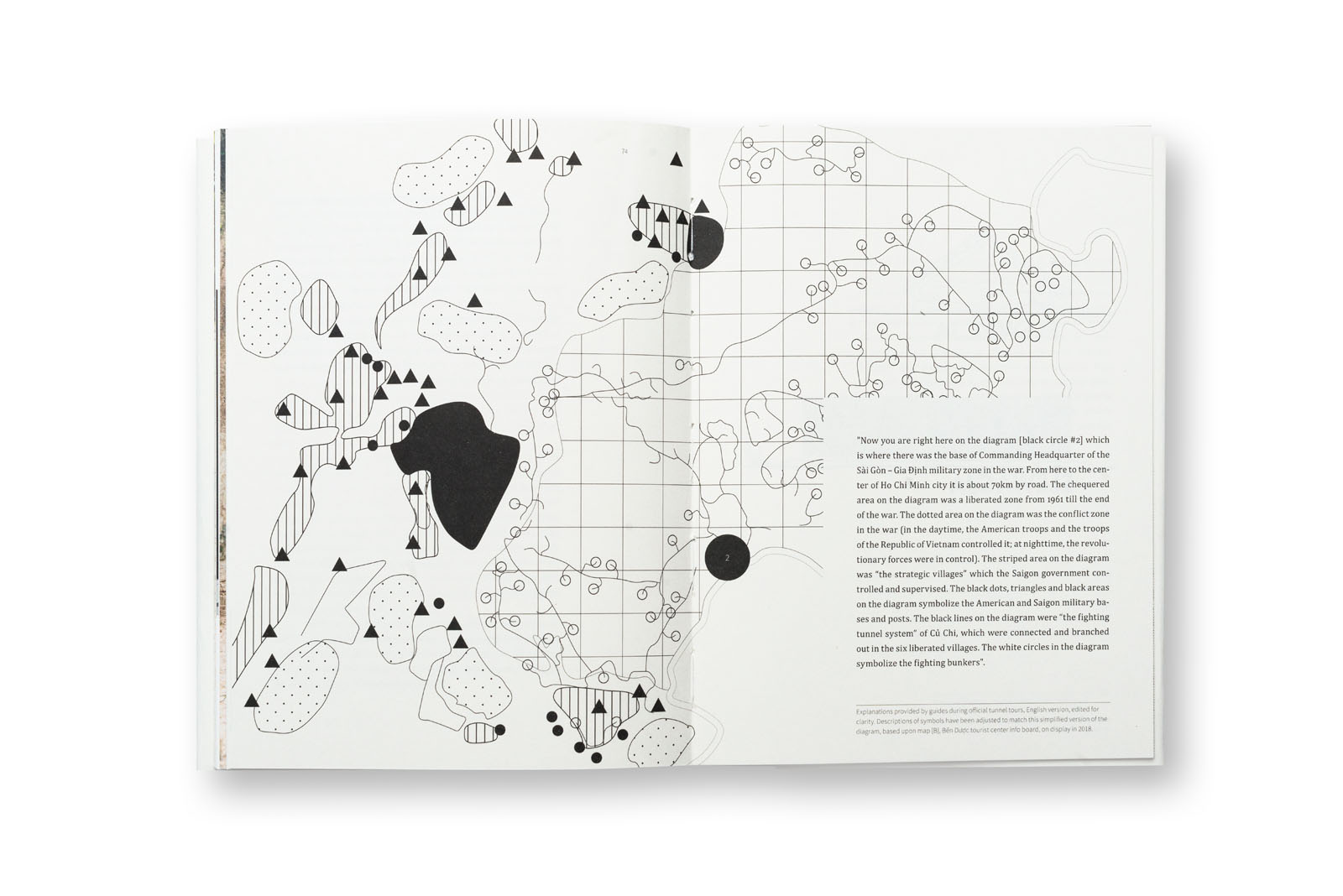

The modern-day pathos of recruit training, tourists’ fantasies triggered by traps set for them – these mount up around the preconceptions of the huge maze of corridors, the parallel world of tunnels connecting hospitals, schools, command centres and cinema theatres, all this hidden underground. The 250-kilometer network of tunnels built on three levels ensured survival at the time when life on the surface was impossible, when American bombardments turned the Cu Chi province into rubble devoid of plants, animals and people. The tunnels, expanded to the size of an underground city during the American War, were the answer to the brutality of the conflict, materializing in the form of secret corridors which were narrow, dark and crawling with insects.

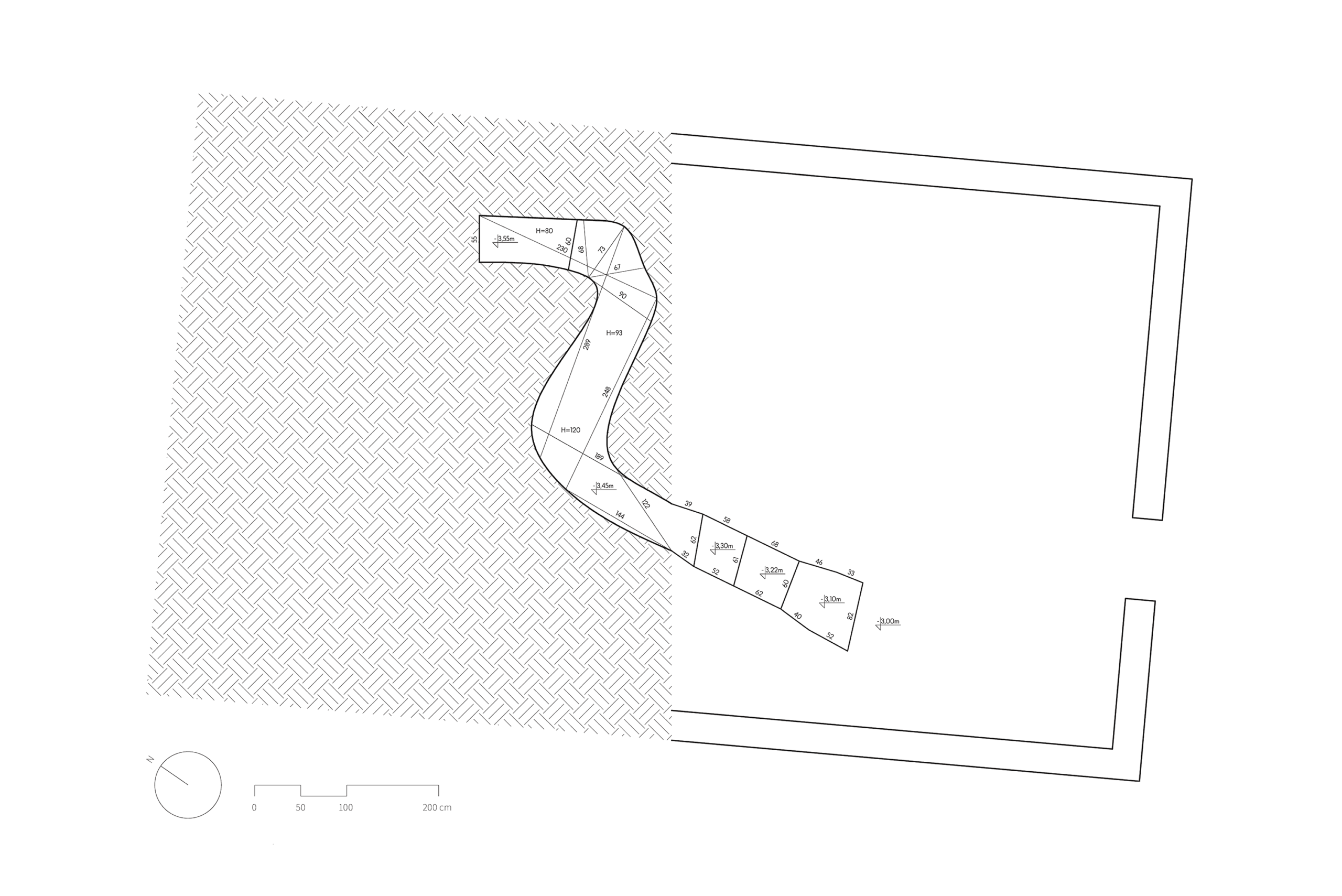

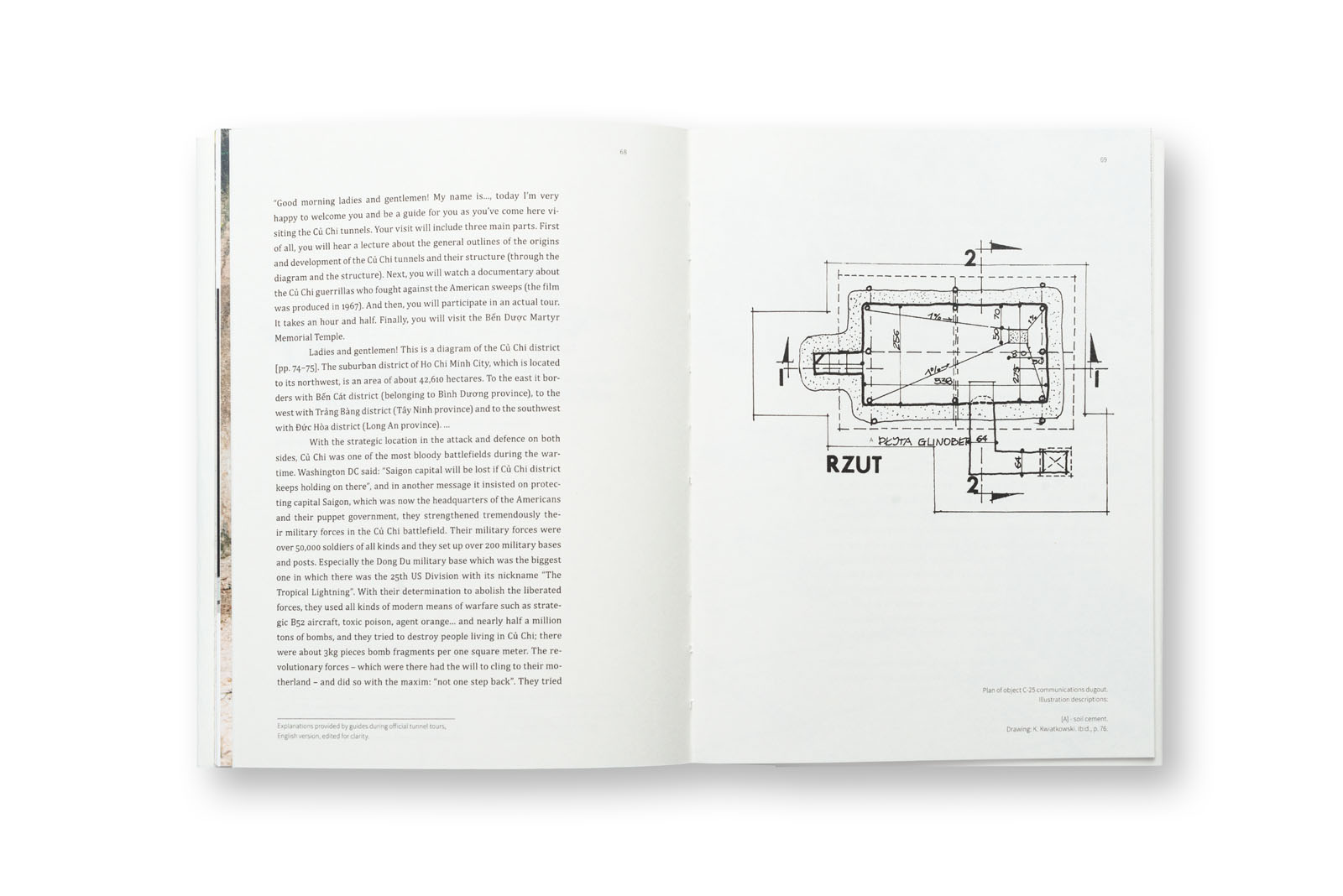

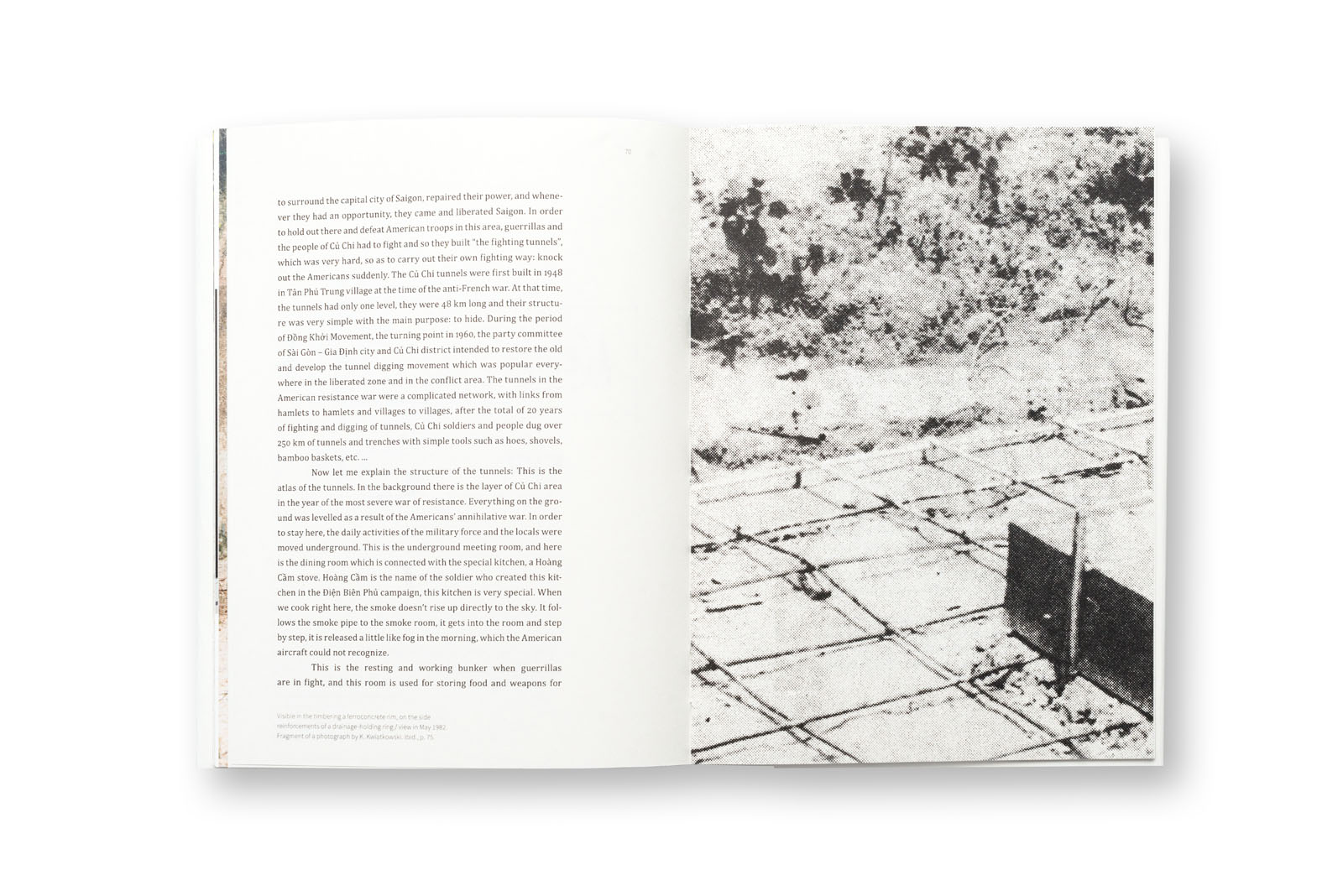

In 1981 a Polish-Vietnamese heritage conservation mission gave an impulse to transforming the tunnels into a symbolic structure by developing preliminary methods of securing and reinforcing fragments of this obscure construction. That was the first post-war attempt to rebuild the architectural heritage of Vietnam. The apparently technical task in fact constituted part of the process of adapting war-time history to the preferences of a modern audience, which was one of the most important historical policy projects of that time. After all, the secrecy and inaccessibility of the corridor network determined the character of this reconstruction – they initiated the process of replacing the material remains of the past with their models. As a matter of course, the underground tunnels turned out less useful than people’s preconceptions of them.

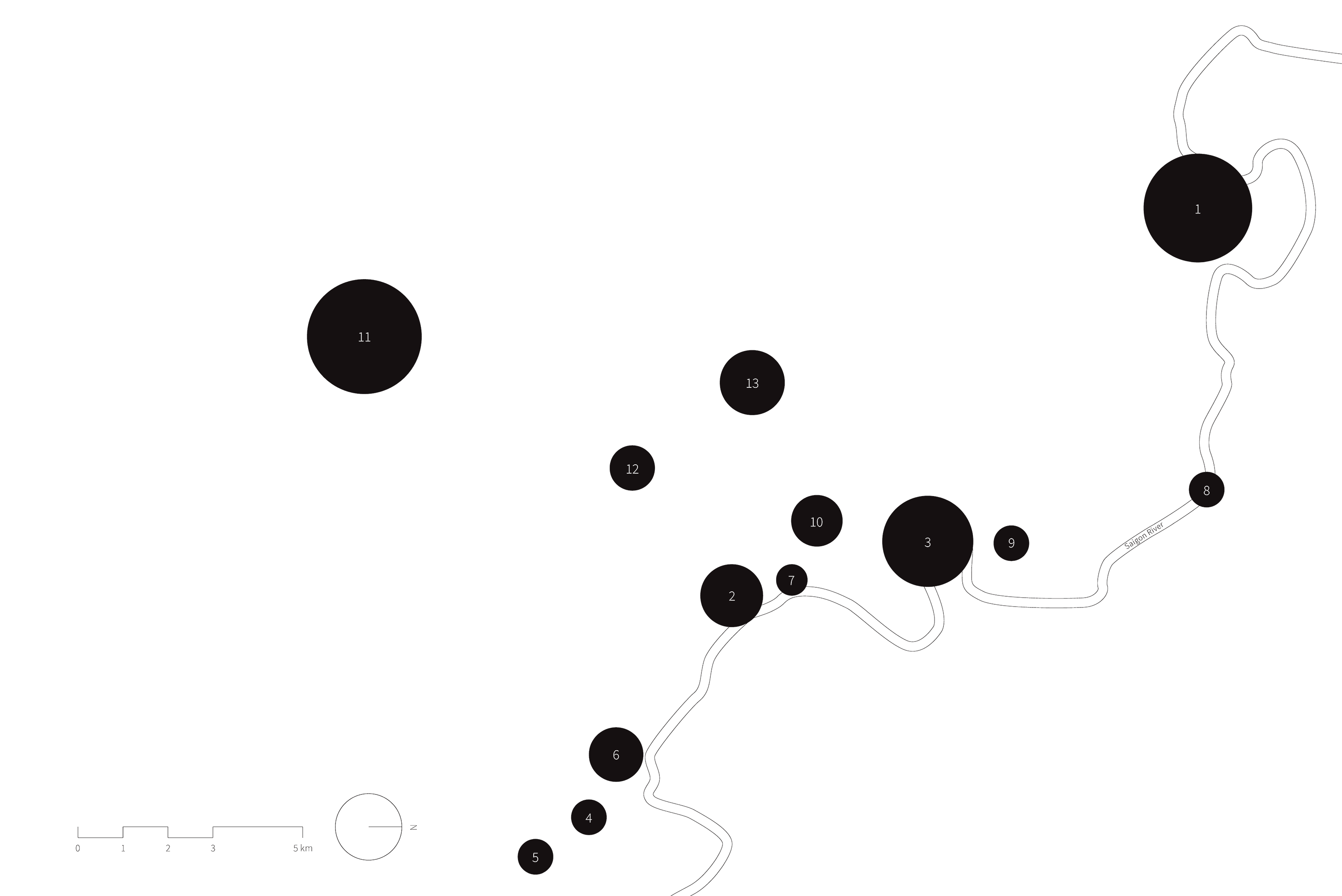

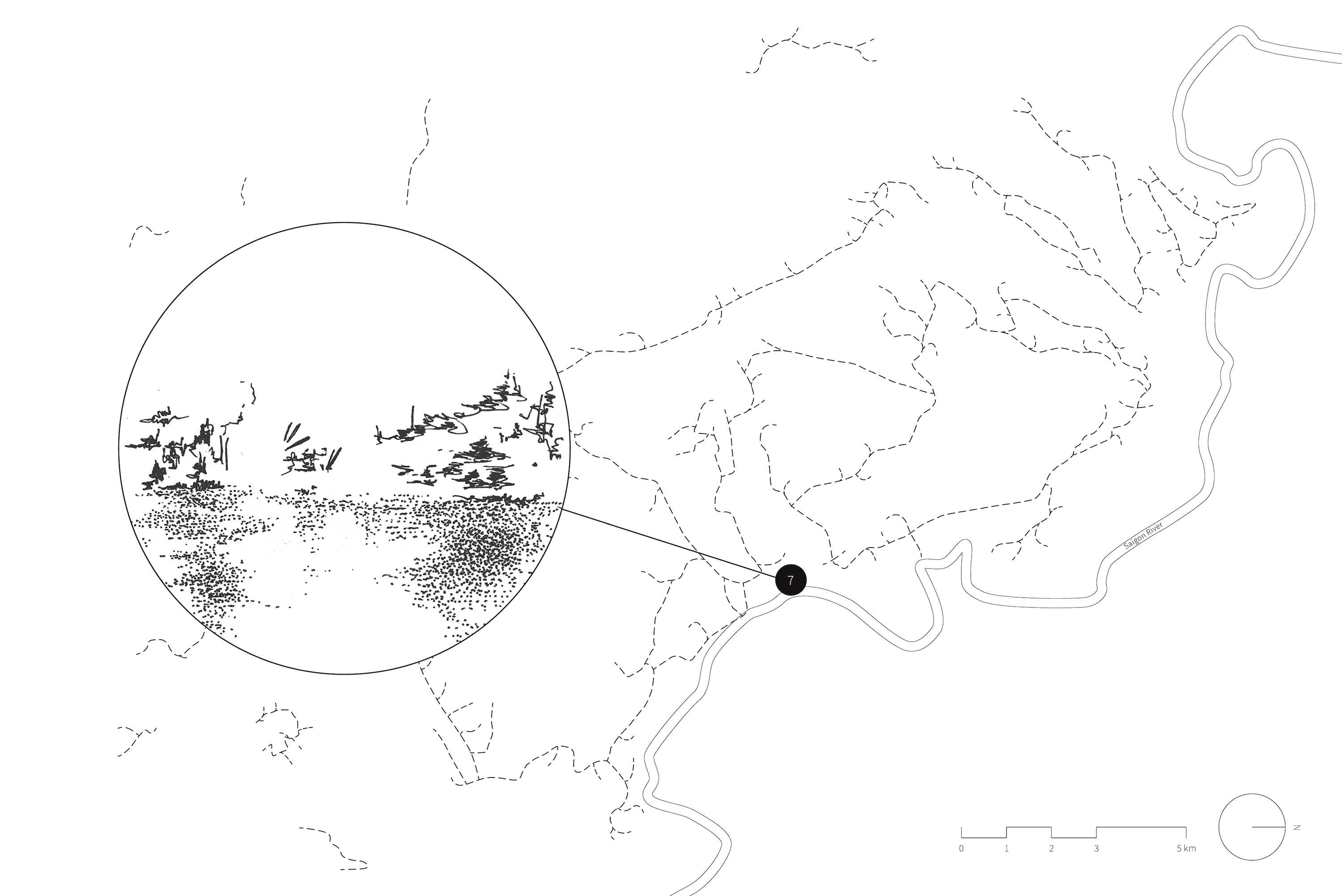

After nearly 30 years since the first revitalization efforts, we follow further steps of this adaptation, and so fragments of the corridors acquire the properties which facilitate the work of imagination; mock-ups appear, ventilation is installed, tourists pop out of camouflaged mock manholes. Images of the underground world are built by visitors, they adapt to travel agency brochures and school trip requirements, while urban legends feed on military secrets and propaganda.

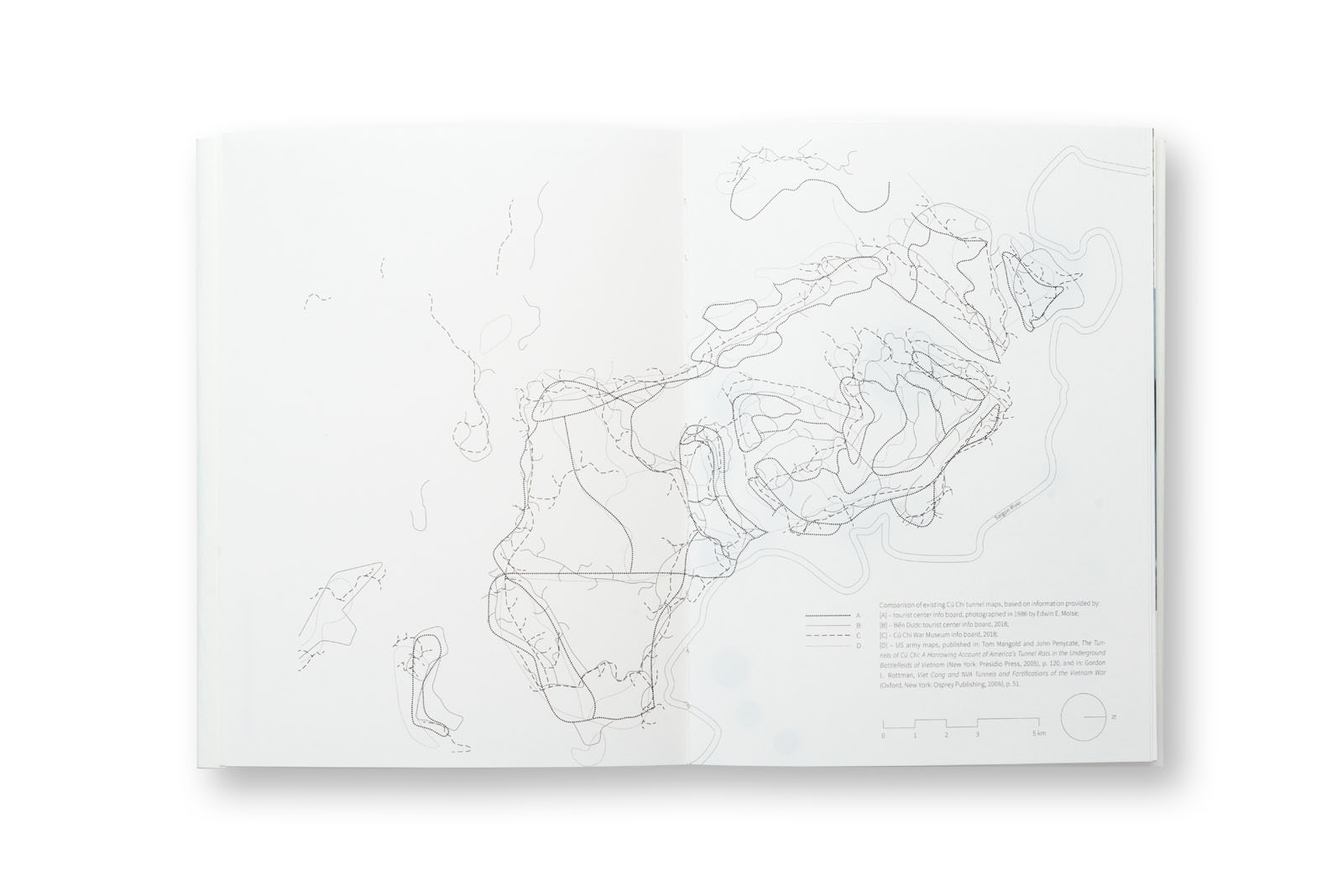

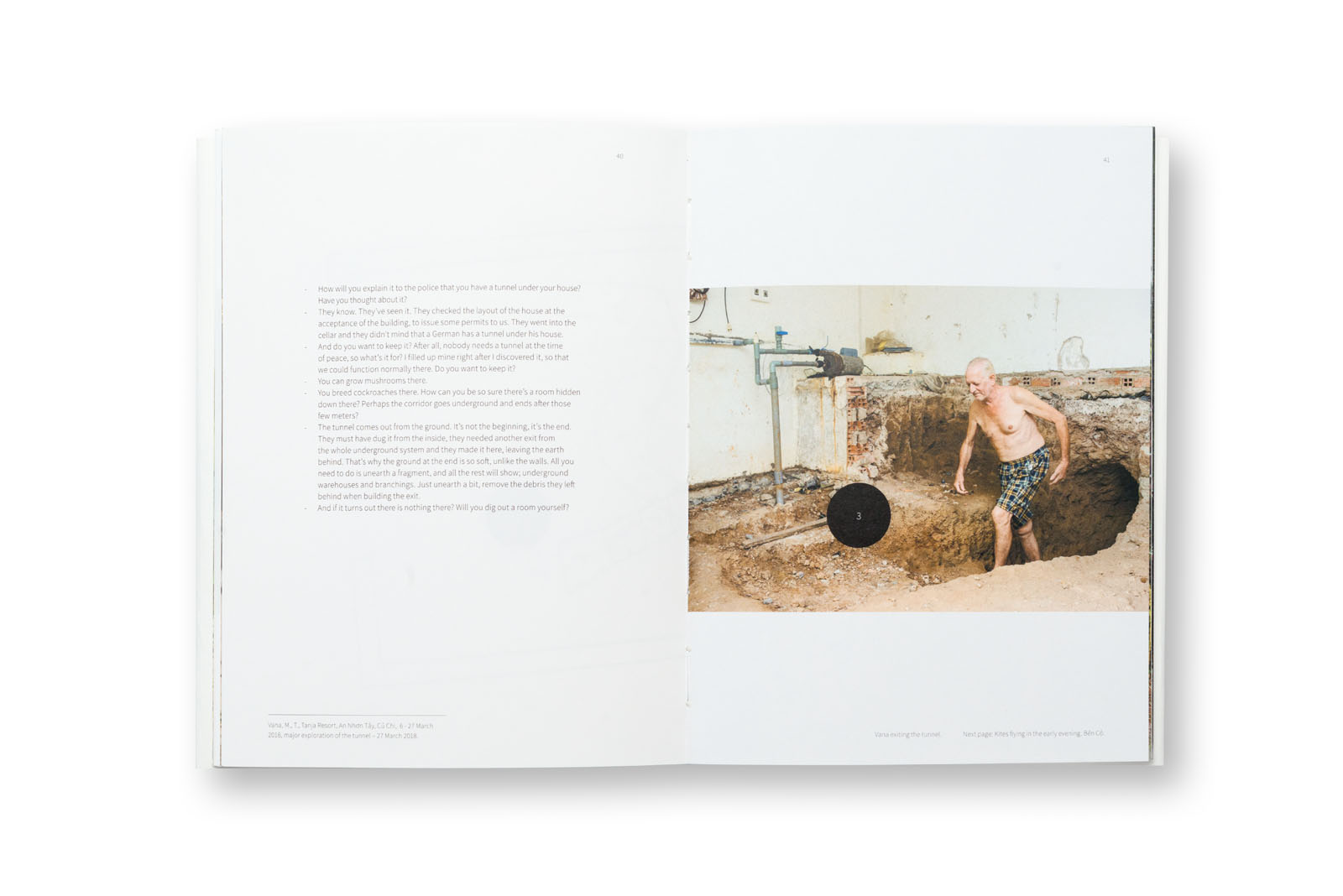

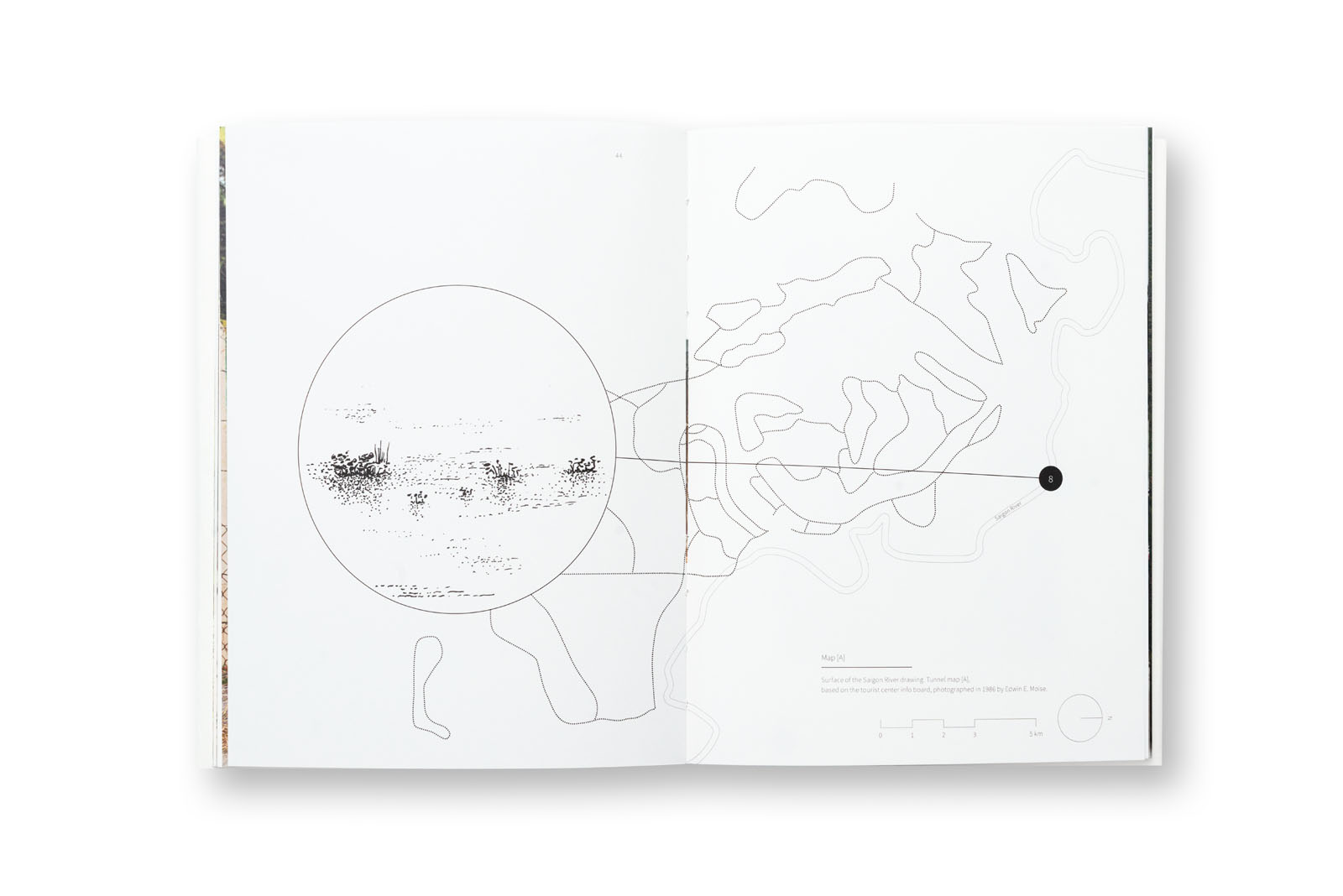

At the same time, these fantasies help blot out memories of Cu Chi inhabitants, for whom getting rid of ever-present tunnels from underneath their houses and fields was the first stage of raising the province from ruin. For normal life to return, it was necessary to tame the fear of the inhuman structure created by the war, to forget the life of the underground, especially that the tunnels do emerge to the surface on the occasion of a new road being built or a cellar being dug out. From this point of view, any version of history, even the most exaggerated one, locked in the safe framework of a tourist attraction, is better than its brutal memory. The only clue distinguishing the terrain where the remnants of the tunnels are hiding is the official maps, schematically indicating the corridor routes, placed outside the museum-reserve.

Our attention is directed at the contemporary preconceptions of the tunnels for another reason: the illusions of this invisible structure shape the material reality. They attract 1.5 million visitors a year, they have an impact on the forming of special economic zones, they attract investment, consistently changing Cu Chi into a prosperous suburb of Hi Chi Minh City.

Secrecy, though of a different kind now, is still the fundamental principle of the tunnels’ effectiveness.