Exhibition views of Zoological Archive, displayed at:

Biennial of Photography in Poznań, PL, 2013

Looking for context “[It] is only the arrangement and management of a Repository of Subjects of Natural History, that can constitute its utility. For if it should be immensely rich in the numbers and value of articles, unless they are systematically arranged, and the proper modes of seeing and using them attended to, the advantage of such a store will be of little account to the public”. (2)

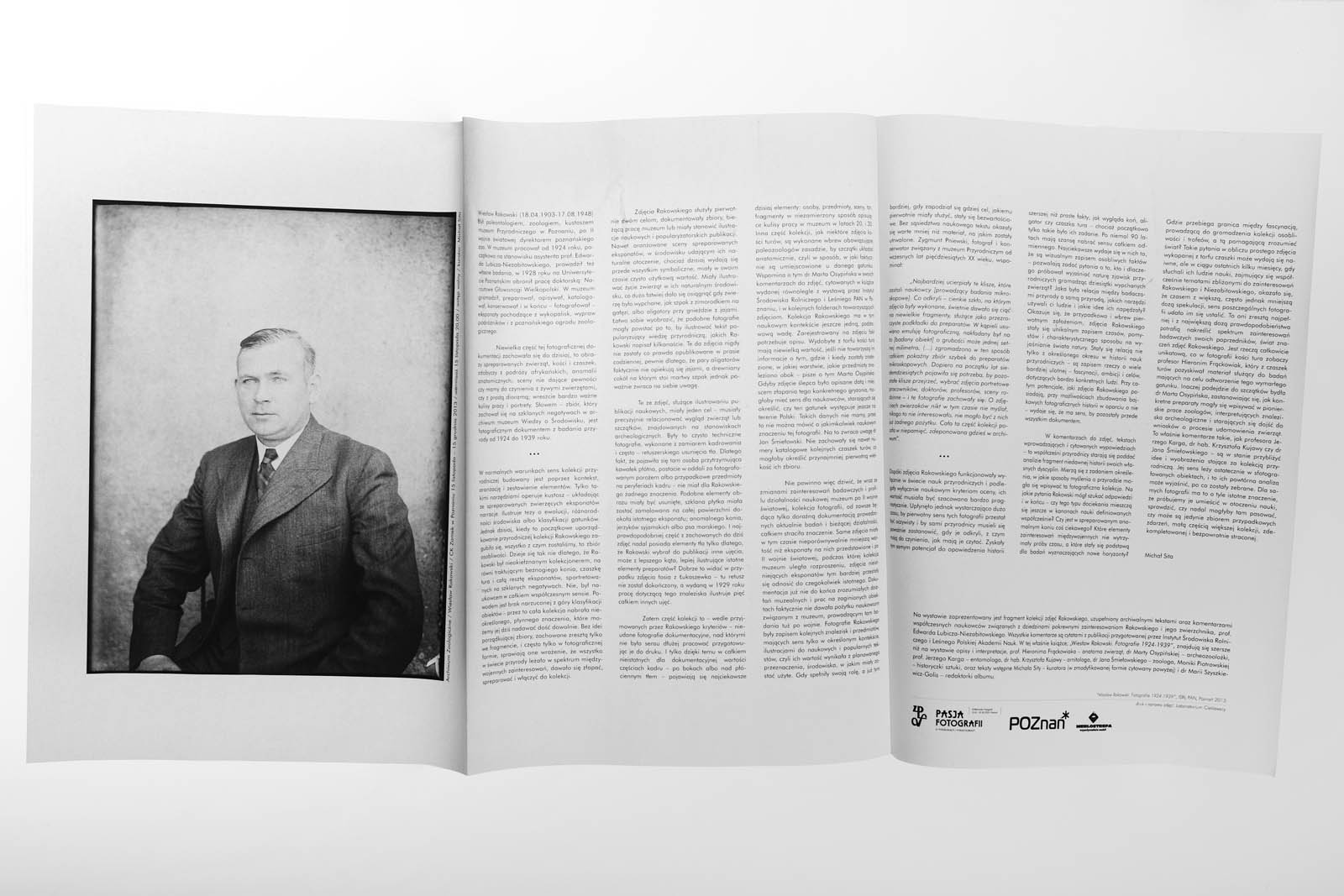

This has been obvious to museum attendants as from the era of the Enlightenment. The sense and meaning of any collection related to natural sciences is always built through proper context, order and suitable combination of artifacts. Those are the only tools available to a curator who attempts to build a narrative out of prepared exhibits. Depending on ambition, commitment and the available resources or theories he (in this case Rakowski) considers worth publicizing, the curator can then illustrate the theories about evolution and the diversity of the flora and fauna inhabiting particular ecosystems along with the ways they operate in those habitats. He may also arrange the collections in a way that corresponds to the accepted classification of species. Those are the three basic strategies of creating meaningful exhibitions in present-day natural history museums. (3) The curator has the qualifications to decide that the exhibits, collected painstakingly and with a great deal of effort, often during several centuries, will be used to communicate specific information or to educate the audiences in a particular scope of interest.

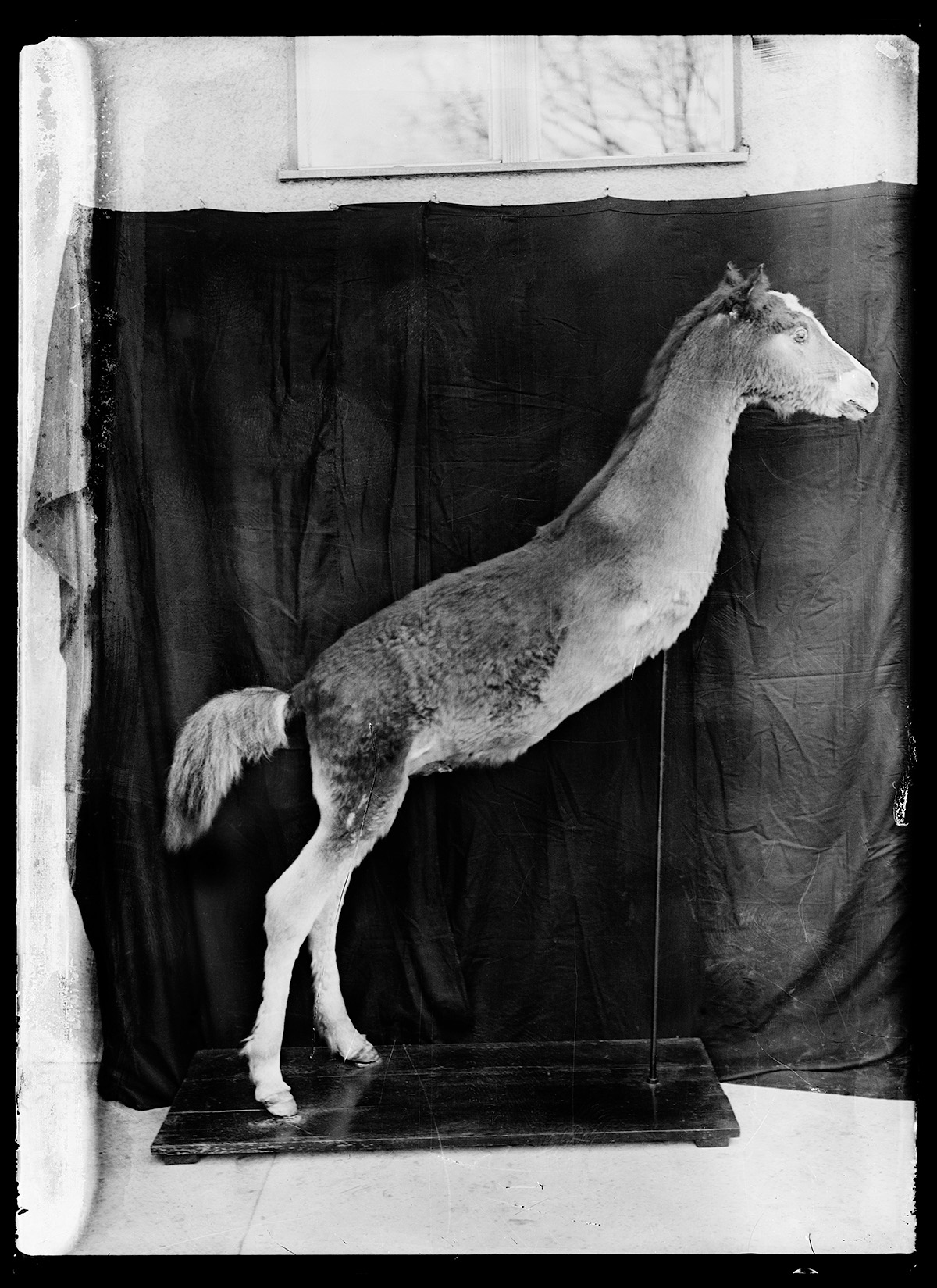

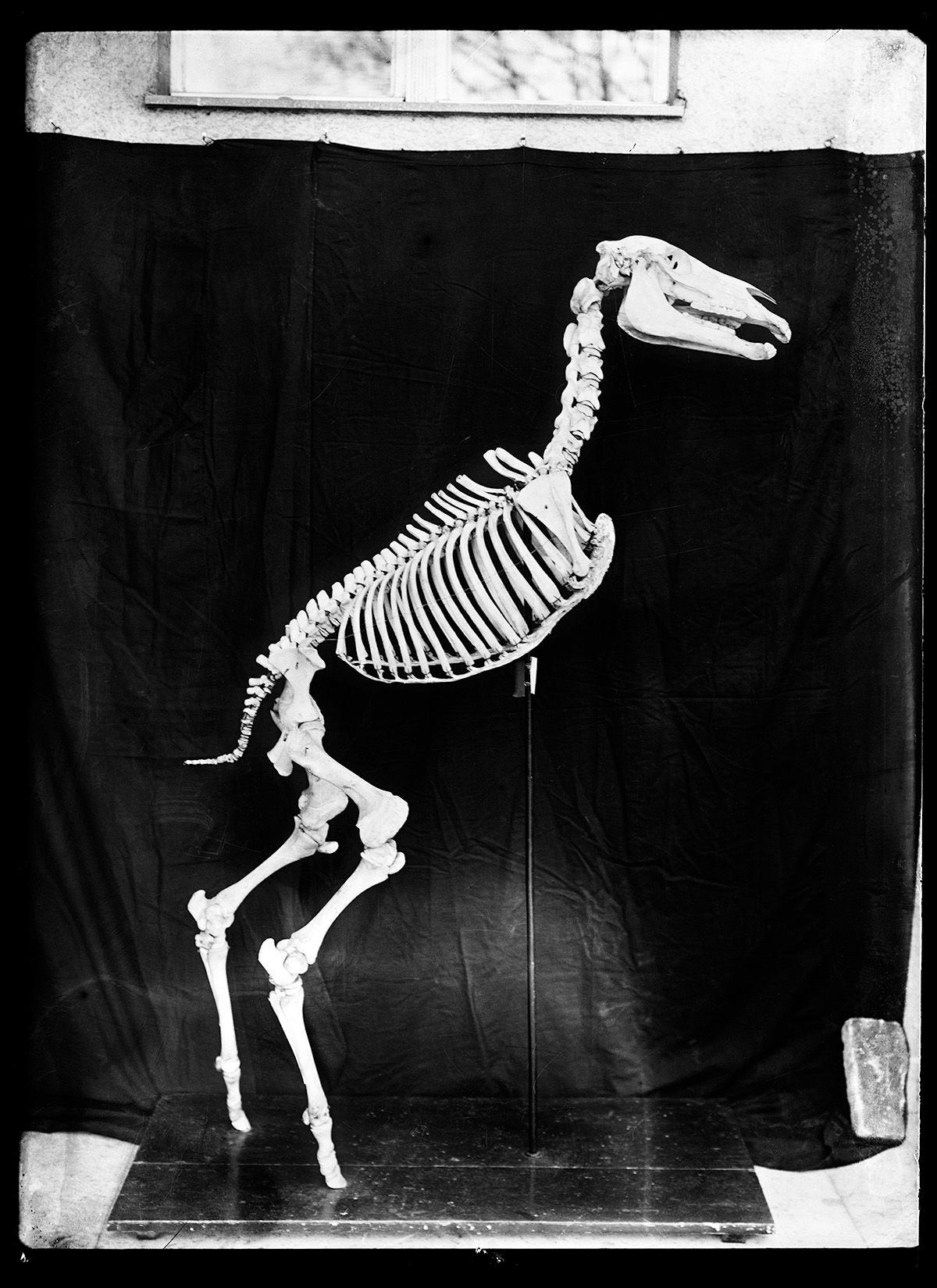

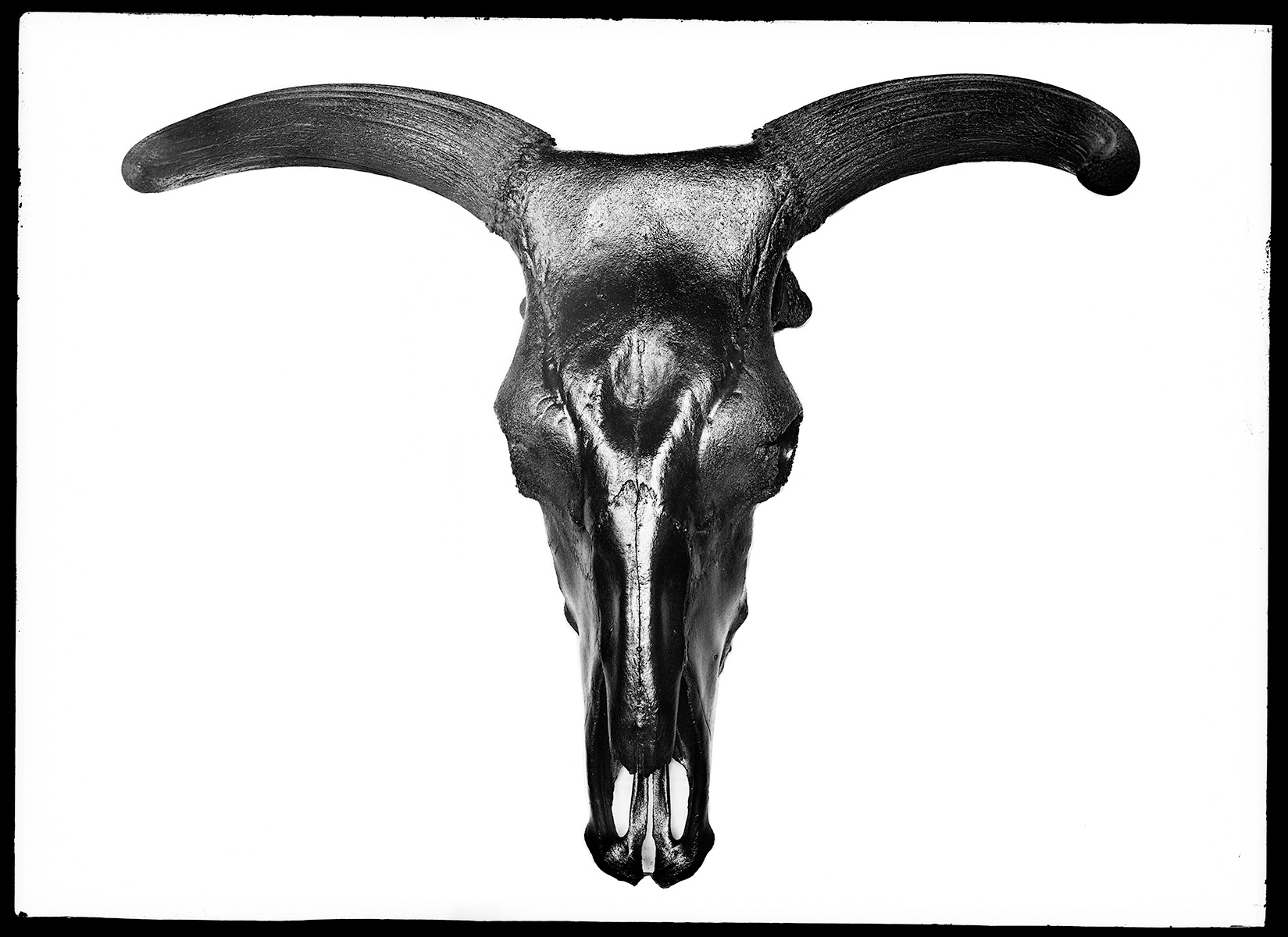

Today it is no longer possible to recreate the initial order of arrangement of Rakowski’s documentation related to nature and life sciences and the context of individual photographs can only be established with a great deal of approximation. All we are left with is a treasure trove of old curiosities cabinet that resembles the much earlier eras. It is not because Rakowski was a compulsive collector who treated with equal reverence a legless horse, a skull of the aurochs and all of the rest of the exhibits captured on the glass plates. On the contrary, he was a scientist in the present- ‑day sense. The true reason is the lack of any pre-determined classification of the objects which means that the entire collection has acquired an indeterminate, fluid meaning which we can add to the collection at will. Without one supreme idea or concept to systematize the collection, which incidentally has been preserved only in part, and very often only in the shape of photographic images, the hoard gives the impression that virtually everything remained within the scope of interest of the explorers, everything that they were able to capture, prepare through taxidermy, and add to the collection inventory.

This seems reasonable especially because the range of interests shown by the Natural History Museum was extremely wide. Rakowski himself commented: “There are three types of museums devoted to natural history. There are the regional museums which collect specimens of flora and fauna peculiar to the particular region only (…). Secondly, there are national museums which hold collections for the entire country or at least a larger part of it (…). And finally there are the general museums which hold specimen collected all over the entire globe. This is the type of museum found in London, Berlin, Brussels, New York etc. This is the type of museum (…) that (…) the Natural History Department of the Museum of Wielkopolska in Poznań belongs to”. (4)

So if the existing photographs show pieces from the collection which comprised specimens from the entire known world of nature, no less, what did Rakowski want to convey through his collection and its photographic images?

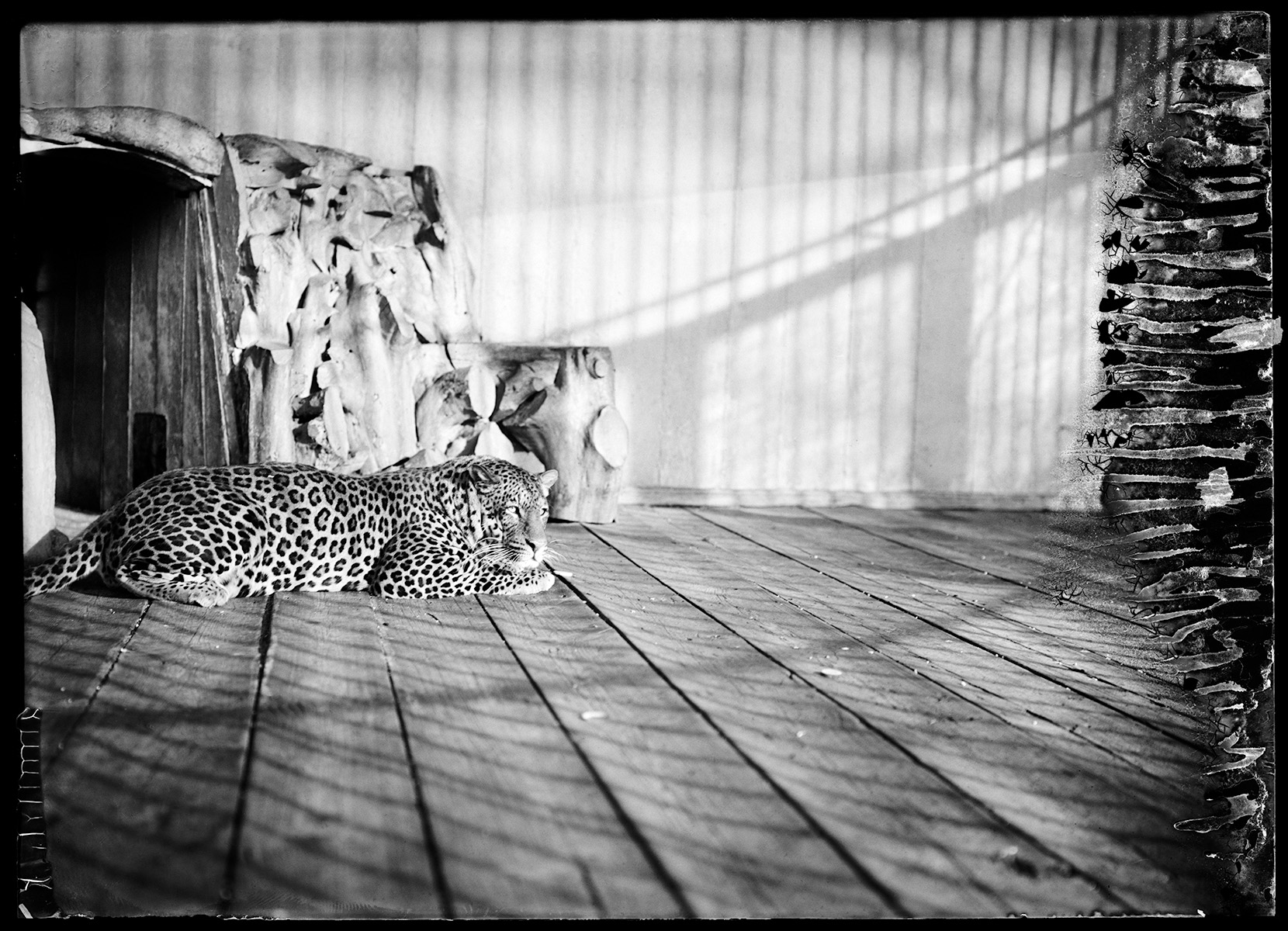

Photography in the service of science? Rakowski’s photographs originally served two purposes. They documented the collection and the nature of the current work at the Museum. They could also be used to illustrate publications, both scientific and those aimed at popularizing science. Even the arranged scenes involving specially prepared exhibits, in the environment that depicted their natural habitat, however symbolic they appear today, had a very usable or utilitarian value in their own time. Rakowski’s mentor, Professor Lubicz-Niezabitowski, in his own book published in 1929 and containing photographs of animals from the Poznań ZOO, outlined the idea of taking photographs of this kind– this passage very aptly relates to the original significance of Rakowski’s photographs depicting arranged scenes:

“When photography was introduced (…) photographs of animals started to appear increasingly more often, depicting precisely their forms and movements, and soon artists started to use them too. However, photographs of animals have not become as common as might have been expected. (…) Because taking photographs of animals, even those in captivity, requires a lot of patience and effort, while the environment where those animals are found are usually not very conducive to taking good pictures. I believe that publishing such photographs showing living animals may be quite desirable not only for all those who like animals and take interest in them, but also for the benefit of those who teach zoology at schools, for the benefit of artists and hunters, and beyond that, for the benefit of all those who have no opportunity of seeing such living animals”. (5)

It appeared to be easier to portray the life of animals in their natural habitats, when the conditions were appropriate to get a good snapshot – so a stuffed animal was positioned in a falsified “natural” environment, such as the image of a starling in a company of a kingfisher sitting on a branch, or alligators next to a nest with eggs. It can be easily imagined that they were created in order to complement one of the many of Rakowski’s articles written to popularize knowledge about nature (6). These two particular photographs have never been published in the daily press, possibly because in reality pairs of alligators never tend their eggs, while the stuffed kingfisher being positioned on the wooden stand is much too obvious. However, the cobras could have been excellent in serving Rakowski’s purpose.

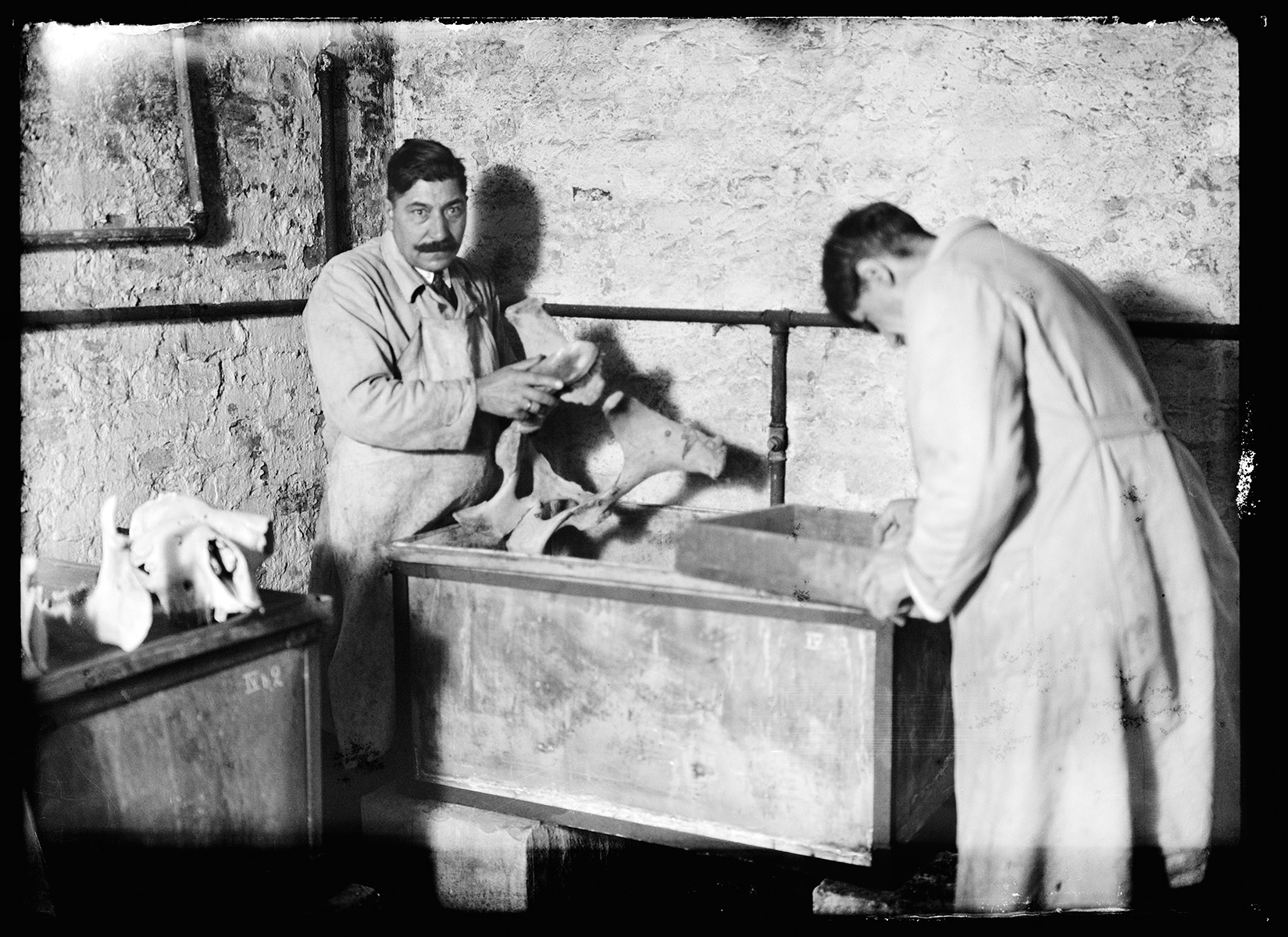

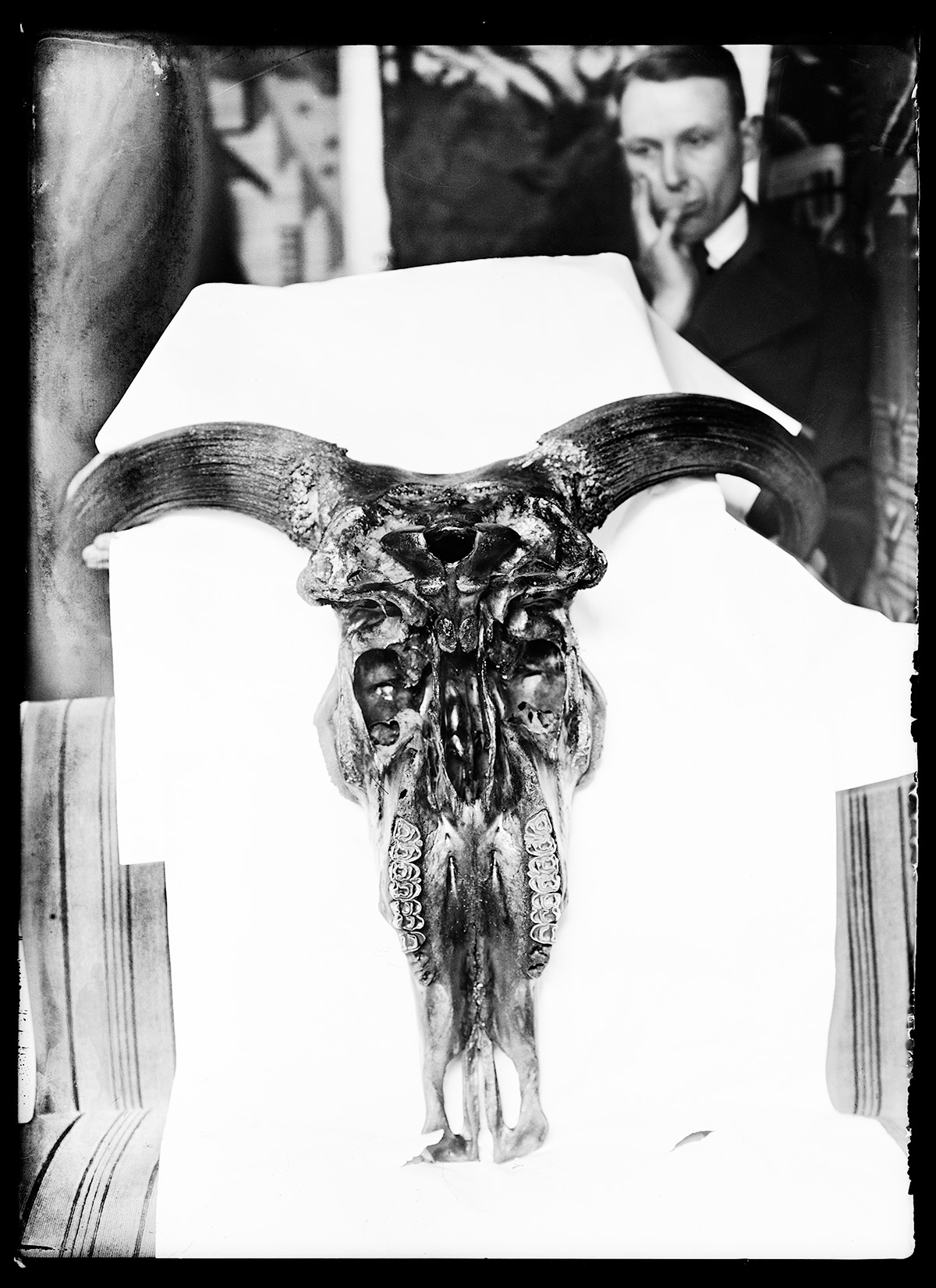

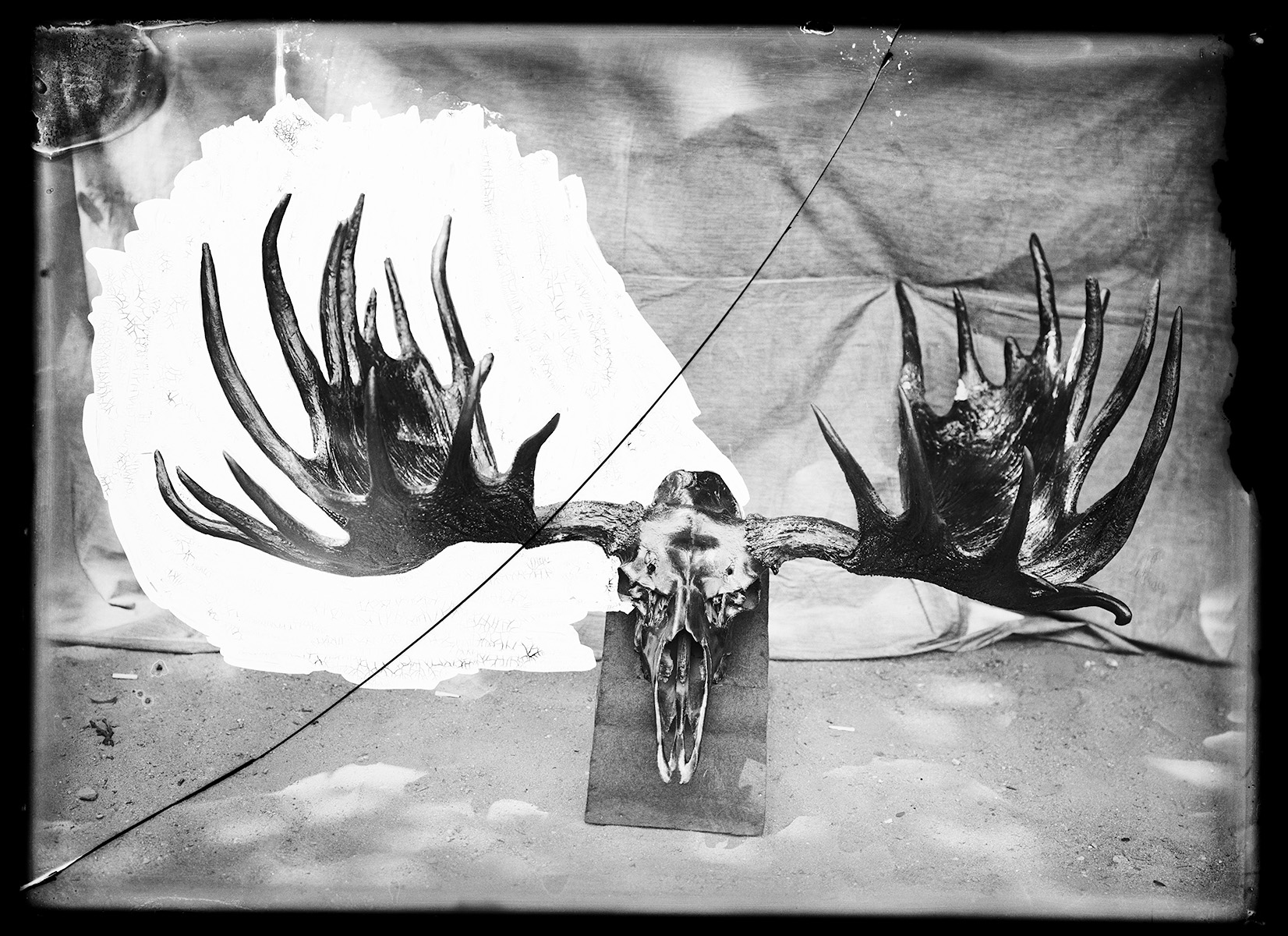

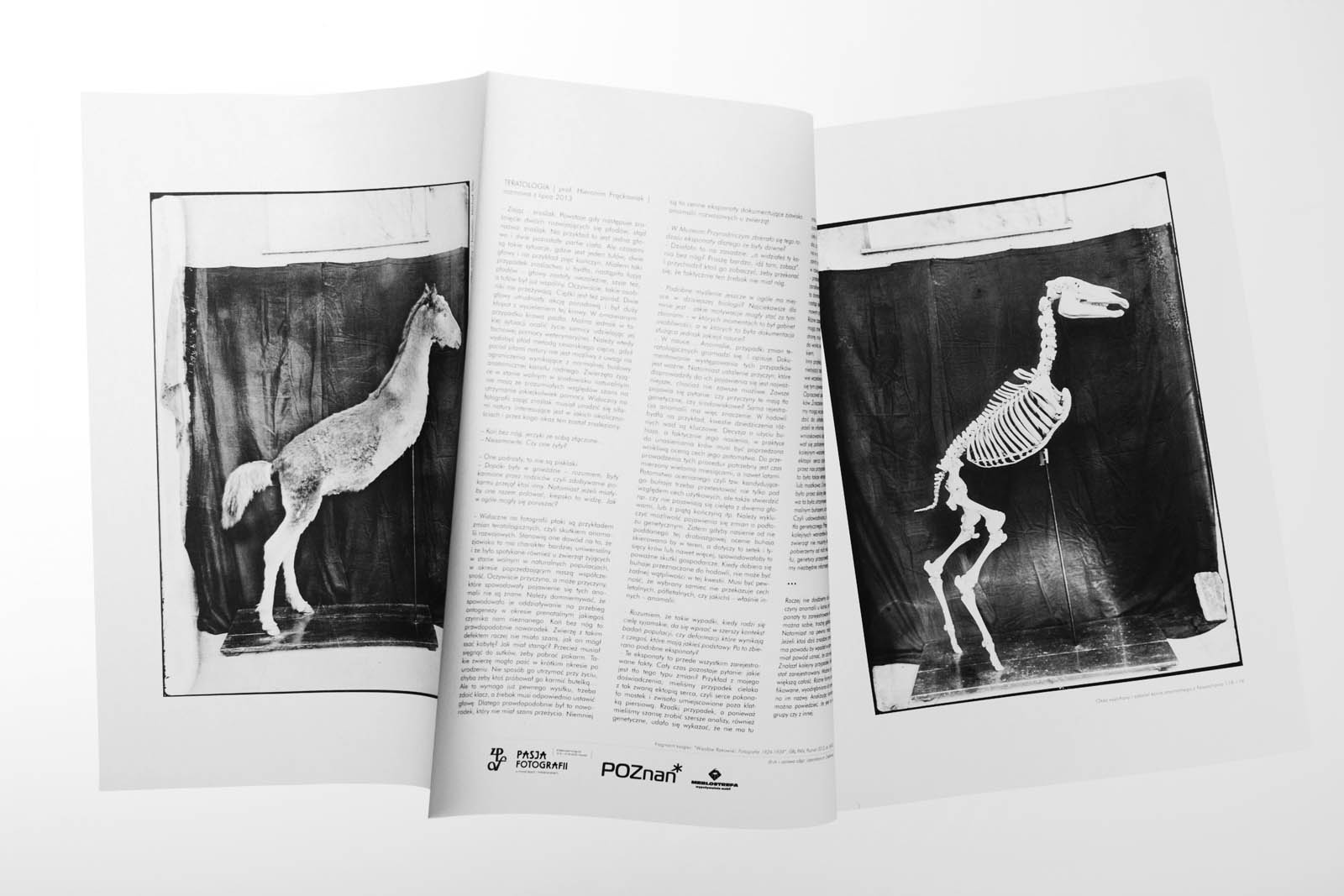

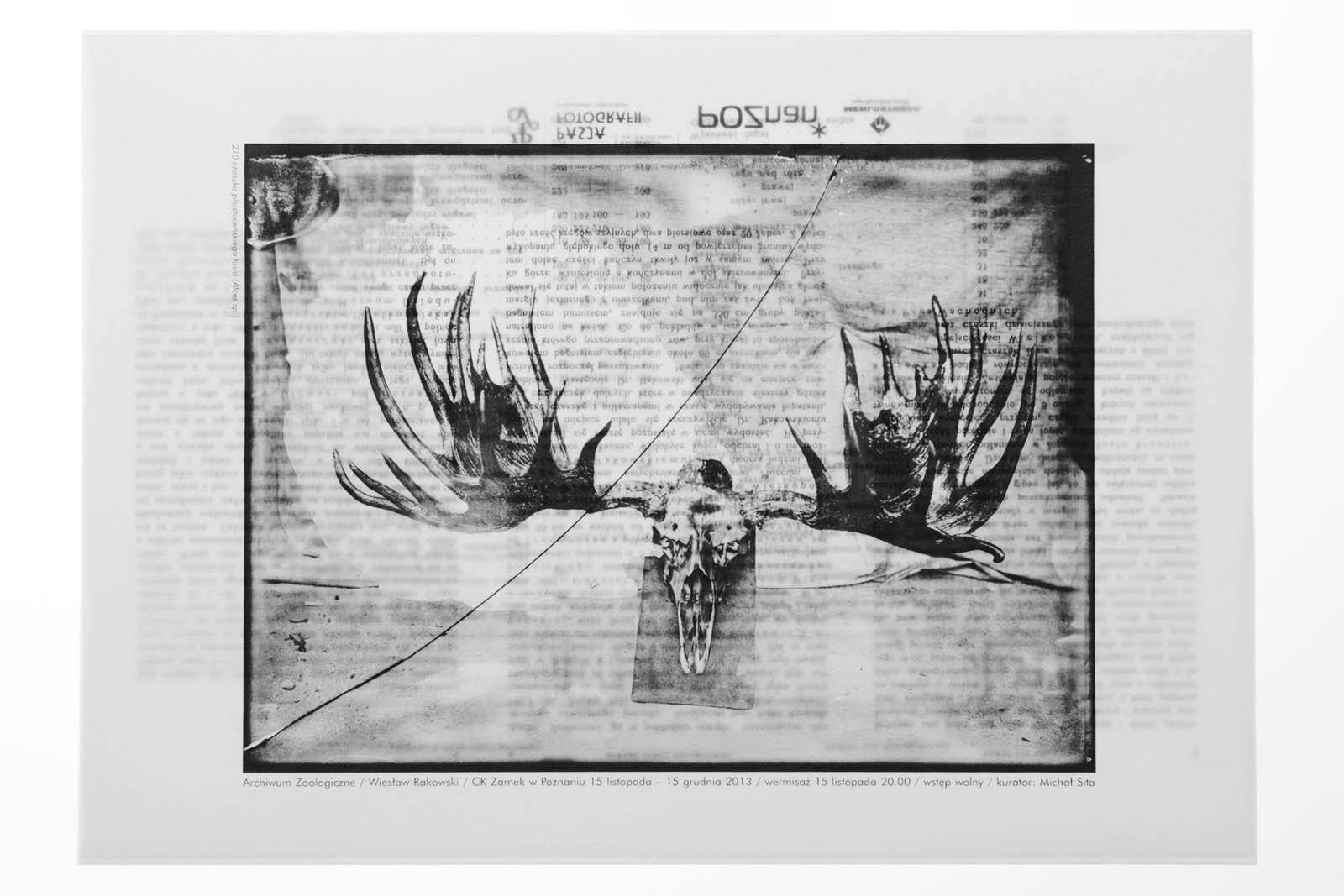

The photographs used to illustrate scientific publications had one definite purpose: they were meant to represent very precisely the animals or the animal remains found in archaeological excavation sites. Those shots were purely technical, made with the intention of precise framing and quite often with a view to removing the background by retouching. For this reason the fact that a person holding a sheet was caught in the frame, or human figures can be seen in the distance behind a set of antlers did not matter at all for Rakowski. Such details in the photograph were to be removed anyway from the glass plate which was supposed to be carefully painted over all around the photographed object; the anomalous hors, Siamese swifts or the harbour sea. And most likely some of the preserved photographs still retain some elements of the background only because Rakowski selected other images for publication, maybe the ones taken from a better angle to show the details that illustrate the relevant parts of the object in the pictures? This can be seen very well when looking at the picture of the moose found in Łukaszewko – here retouching is incomplete, and the study of the finding published in 1929 has been illustrated with five completely different shots. (7)

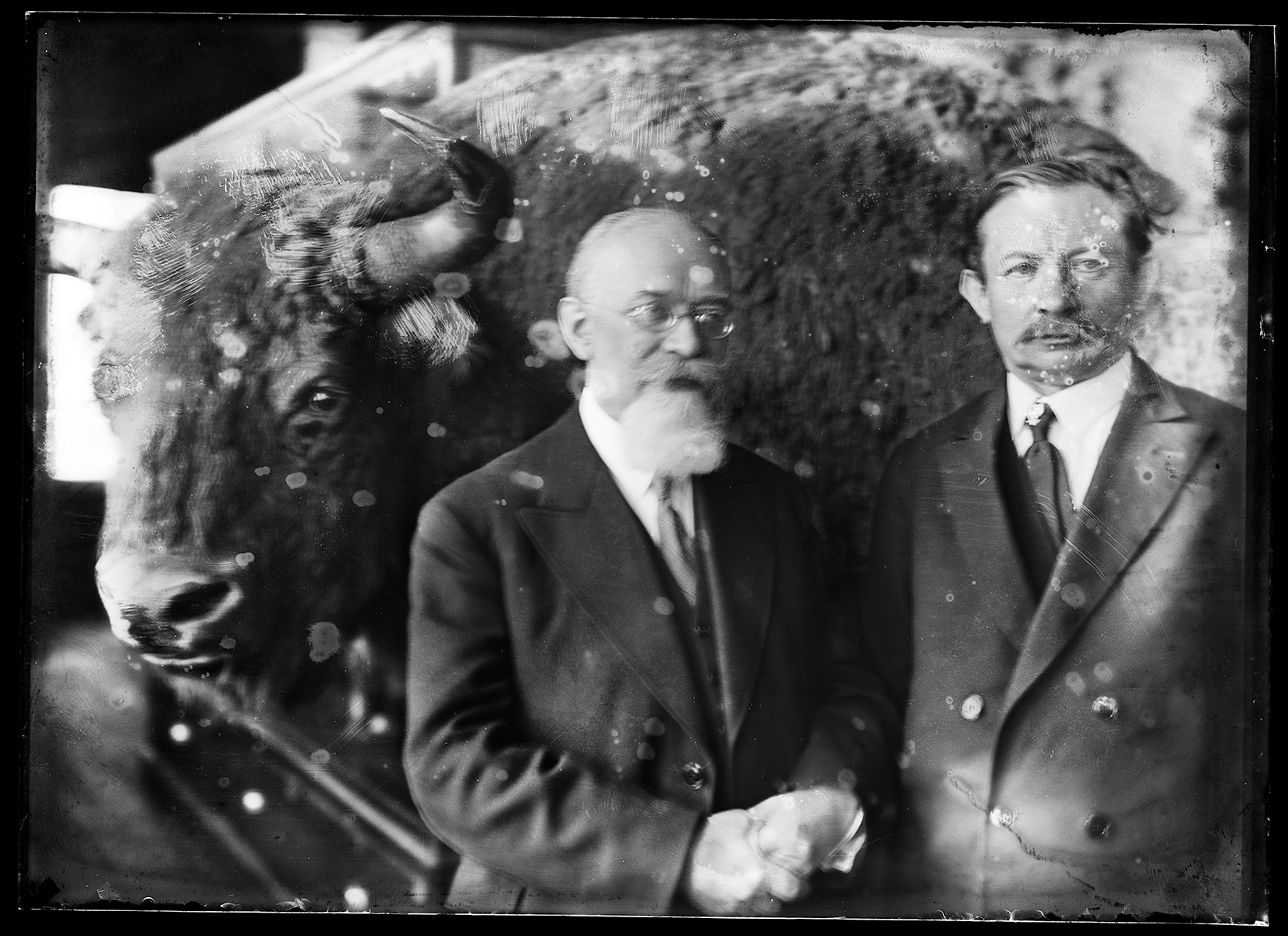

Consequently, according to the criteria adopted by Rakowski, a part of the existing photo collection are just poor snapshots that got rejected from the documentation, which means there was no point in editing them further. (And it is precisely for this reason some sections’ details that are completely irrelevant from the point of view of scientific documentation, are the most interesting for us today, namely persons, objects, scenes, little bits and pieces which unintentionally tell us a lot about the work going on at the Museum in the 1920s and 1930s). Another part of the collection, such as selected photographs of aurochs bones, have been taken in violation of the principle, preferred by paleozoologists, which dictated that such remains should be arranged according to their anatomy, i.e. exactly as they were located in the body of a given species. This point has been raised by Marta Osypińska, Ph. D..

In this context of scientific value, the Rakowski collection has one more fundamental flaw. The fact recorded on a photograph requires a description. The aurochs bones, extricated from the peat mire, are of little value unless they are accompanied by information about where and when they were found, in which layer and what objects were found in the immediate vicinity, as Marta Osypińska pointed out. If the picture of a greater mole rat had been captioned with the date and location where this rodent was captured, it could have been valuable for the researchers trying to establish whether this species still exists in Poland. No such data is available, and for this reason this shot is of little value for research. This valid point has been raised by Jan Śmiełowski Ph. D.. As for the aurochs skulls, even the catalogue numbers for subsequent specimens have not survived — something that could have helped to establish at least the original size of this collection of skulls.

It should not be surprising, then, that with changes in research focus and the changing profile of the Museum’s scientific activity after World War II the collection of photographs, which has always served mainly as documentation of the current research and studies conducted at the given time, has lost its importance altogether. The photographs themselves were of infinitely less value at the time than the exhibits they depicted. After World War II during which the Museum’s collection was fragmented and dispersed, photographs of non-existent exhibits no longer related to anything of importance. The documentation of the museum projects, of which little was known, and of the work relating to the objects that were subsequently lost, had little relevance for the scientists working and conducting research at the Museum just after the war. Rakowski’s photographs were a record of subsequent findings and objects that had significance only in a particular context, to be used as illustrations to scientific publications and popular texts. Their value was closely related to the environment in which they were meant to be used. Once they had fulfilled that role, and more importantly, once the original objective they were meant to serve no longer mattered, the shots lost their value completely. Without being accompanied by scientific text, they were worth less than the material on which they were set. Zygmunt Pniewski, photographer and restorer who has been working for the Natural History Museum since the early 1950s, recalled:

“The items that suffered most were the plates found by the scientists [conducting microscope research]. Those scientists discovered that the fine thin galls plates on which negatives were set, lent themselves nicely to cutting into small strips and making microscope slides for objects for examination. The photographic emulsion was removed by immersing glass plates in a bath. Then an object to be examined, with a thickness of 0.01 mm, was put onto the glass slide (…) thus quite a sizeable collection of microscope slides was gathered. It was only in early 1970s that there was a need to check the remaining plates, to select the portrait shots of the staff, professors, doctors, family scenes, and those photographs have survived. No one bothered about photographs of animals at the time, no one was interested, there was no use for them. This entire section of the collection was consigned to oblivion, stored somewhere in the archives”. (8)

New meanings. Accidentally, the above mentioned collection was recently discovered in the very same archive. As long as Rakowski’s photographs were functioning exclusively in the world of scientific study and were subject only to scholarly evaluation criteria, their value must have been assessed purely pragmatically. However, enough time has passed, making the original purpose of those photographs much less obvious, and making life science researchers wonder, upon their re-discovery, what exactly those plates were and how they should be looked upon. In this way the pictures gained the potential to tell a wider story than just simple statements of facts, beyond what a horse or an alligator or the skull of the extinct aurochs species look like, even though that was their original purpose. After nearly 90 years, they have the chance to acquire a completely different meaning. The most interesting aspect of the photographs appears to be the fact that they are a pictorial record of unique facts – they provoke questions: who and for what purpose attempted to explain the secrets of nature’s processes by collecting dozens of stuffed animals? What was the relationship between the scientists doing research and nature itself, what were the instruments used by those individuals and what ideas drove them forward? It turns out that, by chance and contrary to the original purpose, Rakowski’s set of images has become a unique record of the times, ideas and characteristic approach to explaining the secrets of the world of nature. They are not long a report from a particular period in the history of life sciences. They provide a record of a far more elusive thing: a record of the fascinations, ambitions, purpose and objectives shown by a group of professional individuals.

Even in the light of the tremendous potential that characterizes the collection of Rakowski’s photographs, even with the possibility that they may provide the basis for building fairy tale-like stories, it appears that it is reasonable that they should remain, first and foremost, a document.

•••

In the period between the wars, the Natural History Museum, closely co-operating with the ZOO, had no competition when it came to attractiveness and successfulness in educating the public about the world of nature. The exotic entertainment offered to visitors in the early 20th century was designed to divert and please the public, which had yet to learn about the power of the new media, such as photography, film, and ultimately television. It was here at the Museum that the public was able to directly experience what exotic animals were like. The idea that alongside the educational content, the Museum was to amaze the people by showing those elements of the natural world that were otherwise inaccessible, was part of the carefully planned strategy. It was the golden era of building the Poznań collection when the desire to display another animal species was a valid enough reason to add specimens to the collection. (9) And it is this golden era that Monika Piotrowska writes about in her introduction, sketching portraits of scientists who shaped the Museum since the mid 19th century and talking about their motivation, their objectives and finally about the principles upon which they based their work to inject some sort of systematic order into the collection. Here Rakowski’s photographs prove their great historical value. Only fragments of the pre-war collection of specimens have survived to the present-day. They include unique objects, such as skulls with antlers which belonged to the prehistoric ancient moose and the Irish elk, however, tens of other specimens that had been documented by Rakowski, were lost in various circumstances. It is only thanks to the photographs that we are able to learn what specimens one could found the Museum. Maybe it would be worth trying to establish, based on the photographic material, what actually happened to those treasures?

The Museum was not only a place where exhibits were put on display. It was an institution whose objective was also to do research into the world of animals. For subsequent displays, only those sections of the collection that were related to the wide range of the ongoing research studies were displayed. Such a research centre involves both the popularization of knowledge and doing experiments and taking risks to produce and expand this knowledge. Research initiatives cannot be limited only to communicating information to visitors. For this reason, if we attempt to look for a key to the understanding the collection of photographs that has survived to date, it is not enough to look into the Museum’s history and into the records of the exhibitions or even into the process and logic of collection’s expansion. Some of the exhibits photographed by Rakowski probably never made it into any of the displays. Probably they may have been left alone after initial attempts to illustrate some phenomenon, or an attempt to build a narrative that was subsequently abandoned, or just an impromptu record of the research work conducted at the time.

This is the reason why in the captions to the photographs (found elsewhere in the volume) and in the introductory texts and quotations found later on, contemporary scientists attempt to analyse this fragment of the recent history of their own disciplines. Their challenge is the need to answer the question about the manner of thinking about natural sciences that spawned this remarkable collection of photographic images. What could be the questions that Rakowski was attempting to answer? Does this type of research still belong to the canon of science as defined nowadays? Is the prepared exhibit of a horse with anomalies of any interest at all? Which elements of the researchers’ interest from before the war failed to stand the test of time, and which paved the way for groundbreaking research to broaden our horizons? Where is the border between the fascination which propels us to collect curiosities and rare findings and the fascination which helps us to gain a better understanding of the world?

Such questions, when looking at a simple snapshot of an animal’s skull extricated from peat, may seem naive. However, in the space of the last few months, when those questions were posed to the scientists who are now engaged in research similar to the interests shown by Rakowski and Niezabitowski, it turned out that they managed to establish, sometimes with a great deal of speculation, the significance of individual photographs. After all, these are the people who can best describe the spectrum of research interests of their predecessors, and the world of meaning associated with Rakowski’s photographs, whose attitude is completely unique. Professor Hieronim Frąckowiak would notice this in the picture of an aurochs’s bone. This researcher used skulls of aurochs, often borrowing from the Museum’s collection, to obtain the material later used by Professor Słomski’s team to continue research with a purpose of recreating this extinct species. Cattle remains will be approached somewhat differently by Marta Osypińska Ph.D. who will investigate which of the Museum’s specimens could have been used in the the zoologists’ pioneering researches who were trying to interpret archaeological findings. It is the contributions, such as those offered by Professor Jerzy Karg and Jan Śmiełowski Ph.D., that can help us to understand the ideas and concepts behind this collection of nature’s specimens. Ultimately, its meaning rests with the objects that have been photographed, and it is the repeated analysis of the material that may yield an explanation as why they have been put together. It is important for the photographs themselves because we are trying to place them in a scientific environment, trying to find out whether they would still have a place there, or maybe just to confirm that, after all, they are just a collection of random photographed events and incidents, or a small part of a larger and more valuable collection which is fragmented, incomplete and irretrievably lost.

•••

Further on in the volume, the photographs are accompanied by two types of captions. One type contains commentaries of contemporary scientists and researchers, and those comments establish the potential usefulness of the photographs in the world of science from which they are derived. We also quote a selection of texts written by the staff of the pre-war Museum. In some instances, as is the case with the description of how the ancient moose was extricated from peat deposits (10), they contain direct descriptions of individual photographs. In other cases they are more loosely connected with the photograph. For instance, Professor Niezabitowski was explaining in 1924 (11) that contrary to popular belief, the bones found in Carpathian caves are the remains of cave bears and not dragons. Somewhere else Rakowski was explaining what are the leaders in animal families (12). In this way, not only using the photographs alone but also referring to their environment, we will try to tell more about the era of the past, about the unique methods which were used to study nature. It is only thanks to a lucky coincidence, that Rakowski’s photographs that have been preserved, this story has a very strong visual background, and it may tell us something important not only about the world of nature, but also about the people who studied it.

NOTES

1) Photographs set in glass plates of this size are characterized by unrivalled amount of detail, excellent resolution and various possibilities to reproduce very delicate differences in tone and brightness which is made possible thanks to the large size of the negative. Apart from an unwieldy camera used for shooting and achieving the right exposure, the technique is time-consuming and, in the time between the wars, it was also expensive. For this reasons the shots taken by Rakowski cannot have been taken carelessly or at random, because they required a great deal of preparation and planning to frame the object.

2) Charles Wilson Peale, pioneer of the American collections in the field of natural history, words written in 1800, quoted after: Asma Stephen. Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums, Oxford University Press 2001: p. 191.

3) op.cit., pp. 170–223

4) Rakowski Wiesław. Historia i Zbiory Oddz. Przyrodniczego Museum Wielkopolskiego w Poznaniu (Gajowa 5), in:Kronika Miasta Poznania 1934: 127–139: p. 127.

5) Lubicz-Niezabitowski Edward. Postacie Żywych Zwierząt według własnych zdjęć z natury, dokonanych przeważnie w poznańskim Ogrodzie Zoologicznym, vol. I, Księgarnia św. Wojciecha, Poznań 1927: p. 2.

6) Rakowski’s bibliography of newspaper articles, selected after: Dzięczkowski Andrzej, Wiesław Rakowski, in: Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XXX, p. 533–4, Zakład im. Ossolińskich PAN 1987.; Express Poznański R. 3: 1948 no. 80 p. 4; Głos Wielkopolski R. 4: 1948 no. 80 p. 12, no. 228 p. 4, no. 229 p. 4, Kurier Poznański R. 27: 1932 no. 380 p. 6, R. 31: 1936 no. 182 p. 8, no. 218 p. 8, no. 226 p. 6; Kwartalnik Muzyczny R. 1: 1948 z. 1–4 p. 23, 121; Muzyka Wielkopolska w Poznaniu R. 3: 1928 pp. 174, 178, 179, R. 4: 1928 p. 147, 151, 153, 166. And as quoted the archives of the “Old” ZOO in Poznań: Kurier Poznański of 18 March 1930, no. 591 of 30 December 1931, no. 138 z 25 March 1931, no. 319 of 19 July 1934, no. 306 of 8 July 1936, no. 392 of 26 August 1936, 12 February 1939, no. 231 of 21 May 1939.

7) Lubicz-Niezabitowski Edward. Dawny Łoś wielkopolski, Rocznik Nauk Rolniczych i Leśnych Tom XXI, Poznań 1929.

8) Zygmunt Pniewski, an interview, Poznań 10 July 2012.

9) Asma Stephen. Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums, Oxford University Press 2001; Maria Mytaruk, Cabinets of Curiosities and the Organization of Knowledge, University of Toronto Quarterly, vol. 80:1 2011;

10) Lubicz-Niezabitowski Edward. Dawny łoś wielkopolski, Rocznik Nauk Rolniczych i Leśnych, vol. XXI, Poznań 1929.

11) Lubicz-Niezabitowski Edward. Smoki karpackie i Smocze Jamy, in: Kosmos. Czasopismo Polskiego Towarzystwa Przyrodników im. Kopernika, Lviv 1924: pp. 879- 890.

12) Rakowski Wiesław. Książęta rodu zwierzęcego, in: Kurier Poznański no. 7, 12.2.1939.